‘ô Mia Divinità’- Bilderdijk’s Love Letters

Few love letters are more passionate and profound than those written by Romantic poets like Willem Bilderdijk. The real story of his love life, however, is complex and sadly filled with strife.

Many nineteenth-century writers whose archives are kept in the Leiden University Libraries have written about love. Nicolaas Beets (1814-1903) wrote romantic verses for his later wife Aleide van Foreest, of whom he also kept a dried flower and a lock of hair. These relics must have been of great emotional value to him because he kept them after a short illness took Aleide, a mere 37 years of age, from him in 1856. François HaverSchmidt (1835-1894, better known as Piet Paaltjens), who was born on Valentine’s Day, published poems about impossible love in his Snikken en grimlachjes (1867). No one, however, wrote more passionately about love than Willem Bilderdijk (1756-1831).

The first marriage

In 1784, Bilderdijk met Catharina Rebecca Woesthoven (1763-1828) in The Hague. She was a pretty young woman, with long, blonde curls, blue eyes and a slender figure. Soon they were sending each other ardent love letters. Hers, unfortunately, have not been preserved. In early May 1784 Bilderdijk wrote that he clearly felt that he had lost his heart to her:

Before long, they went beyond words. He regularly paid her secret nocturnal visits. In his love letters, he praised Woesthoven’s enchanting lips and bosom.

After their marriage in 1785, necessitated by Woesthoven’s pregnancy, their love vanished like snow in the sun. Bilderdijk was a difficult, irritable and melancholy husband, who was in a constant state of exhaustion. More than once during these years did he engage in domestic violence. Instances where he physically abused his wife were commonplace, even while she was pregnant or had just given birth. In 1795 Bilderdijk left the Netherlands because he refused to recognize the new Batavian regime, but his decision also relieved him of his unhappy marriage. He left his family behind in The Hague.

The second ‘marriage’

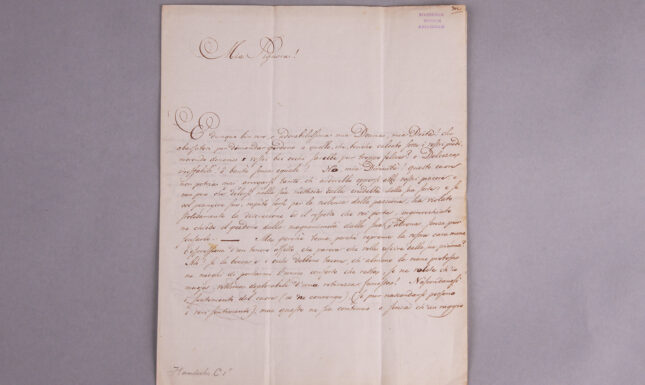

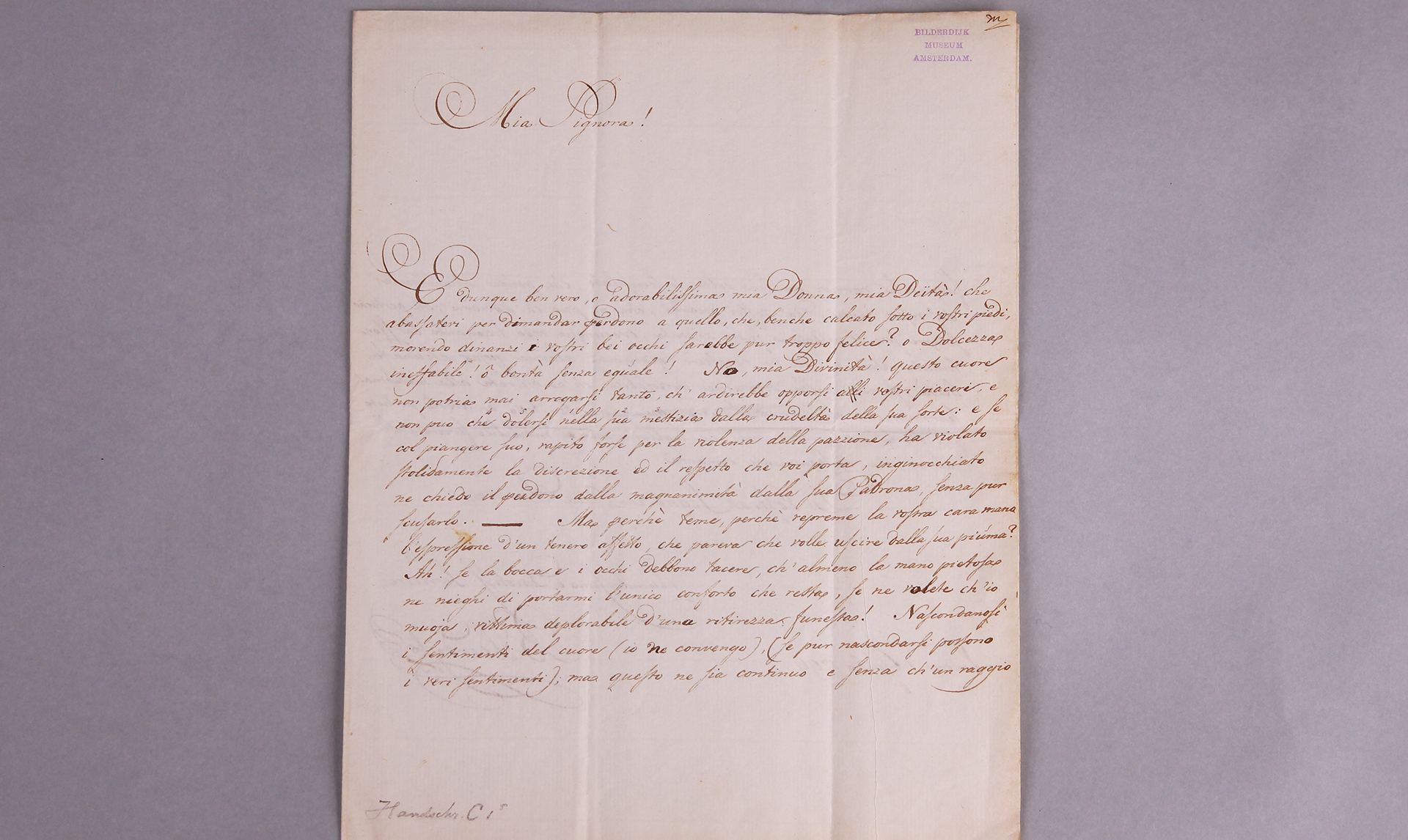

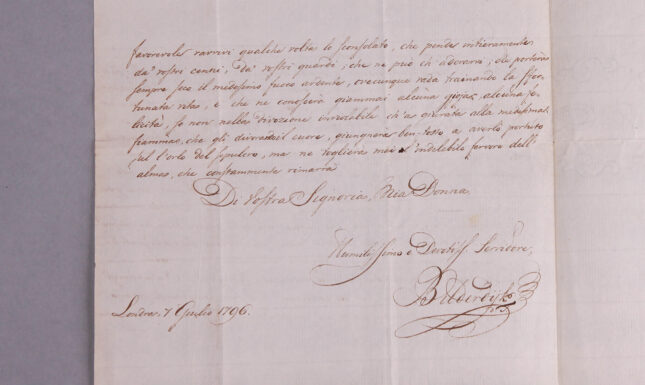

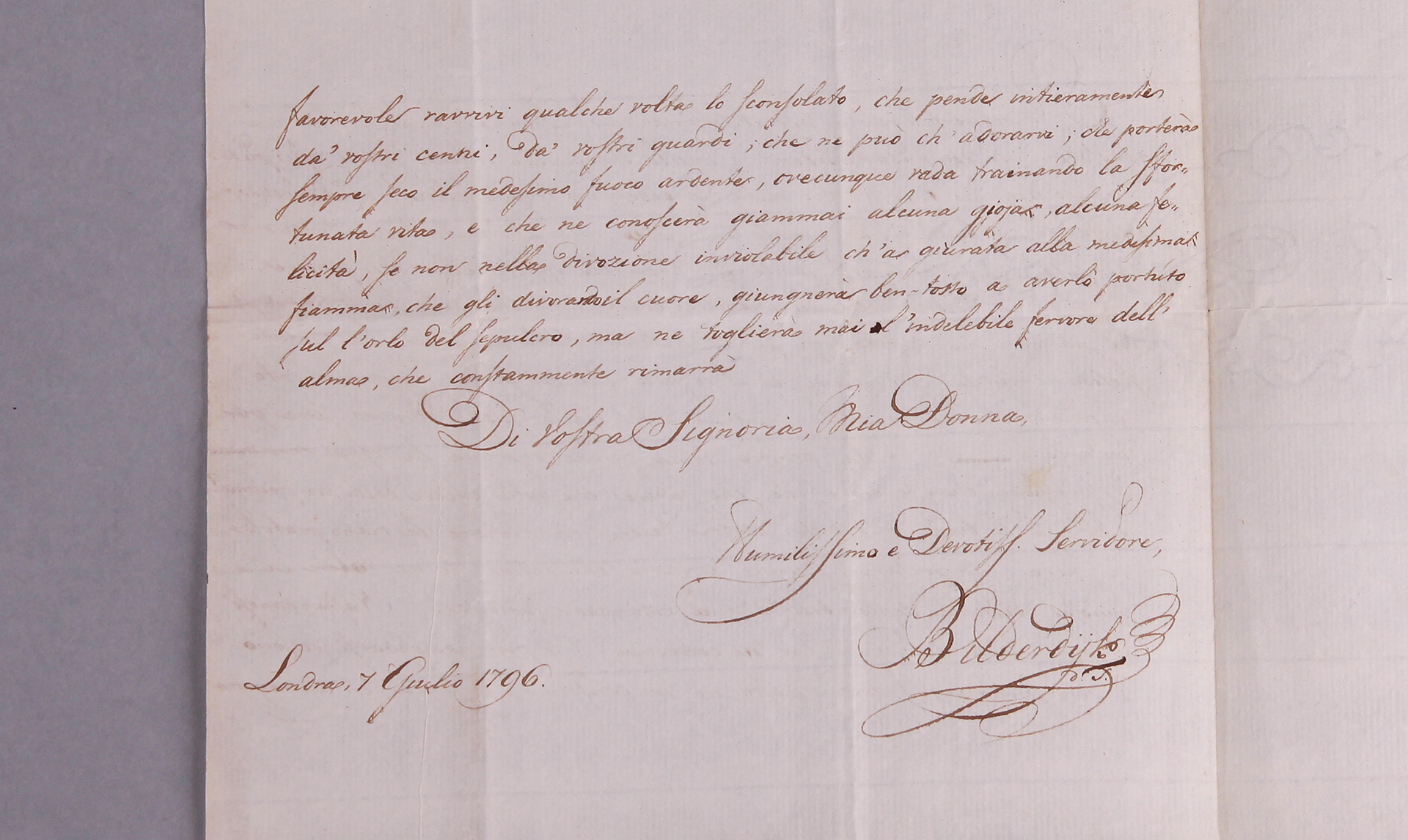

After a stay in Germany, he travelled to London. Here, he became acquainted with the nineteen-year-old Katharina Wilhelmina Schweickhardt (1776-1830), whom he taught Italian. Although Bilderdijk was a married man and nearly twenty years older, he was soon head over heels in love. He sent her passionate Italian love letters, in which he begged her to admit that she loved him as much as he loved her. Thus ‘Il passionato Servo Bilderdijk’ told her:

He asked her to reciprocate his feelings, and she did.

When her parents denied him access to their home, the lovers could only meet secretly. Bilderdijk wrote that she had brought back happiness into his life. If she was not around, he felt miserable. More than once did he try to persuade her to elope with him and leave everything behind, whereby he sometimes threatened suicide. Then she replied: ‘Voi dite che sagrificato la vostra vita – Ah debbio dunque voi accusare, che voi sagrificete la mia vita! Ah che vostri paroli sone inumani!’ (‘You say that you sacrifice your life! Ah, must I accuse you of sacrificing my life! Ah, how inhuman are thy words!’). She instructed him to seek solace in the example of ‘nostro beneditto Salvatore’ (‘our blessed Saviour’).

At the end of 1796, they continued their correspondence in English. On 1 December he wrote: ‘Adieu! dear, angelic… how shall I call you? my murderess? Ah! be that; be everything to me, provided you be not my victim! Live well, and don’t trouble yourself about the health of a dying, starving man, to whom you deny life's support. Adieu!’ When he met her, he was delighted: ‘Adored Angel, ah! a drop of cooling water is Heavenly delight to the thirsty, though it cannot quench the thirst. I enjoyed this delight, my dearest, and my heart is happy, though its wishes are but inflamed and not satisfied.’

Mrs Bilderdijk

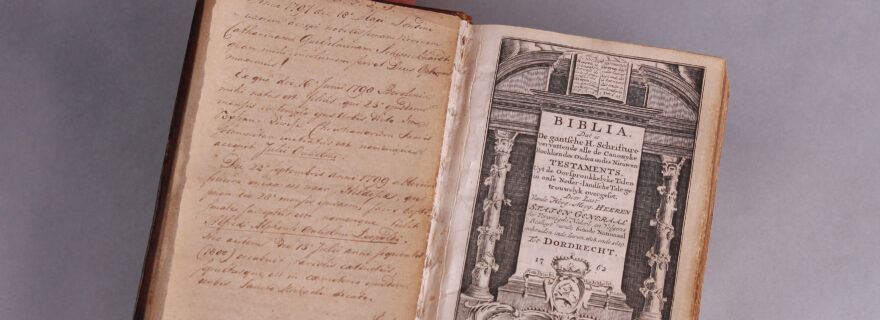

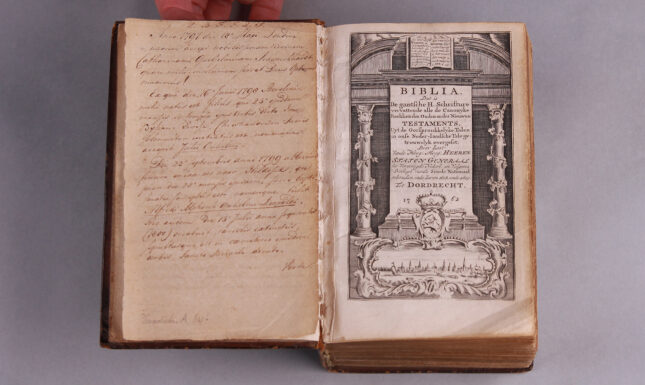

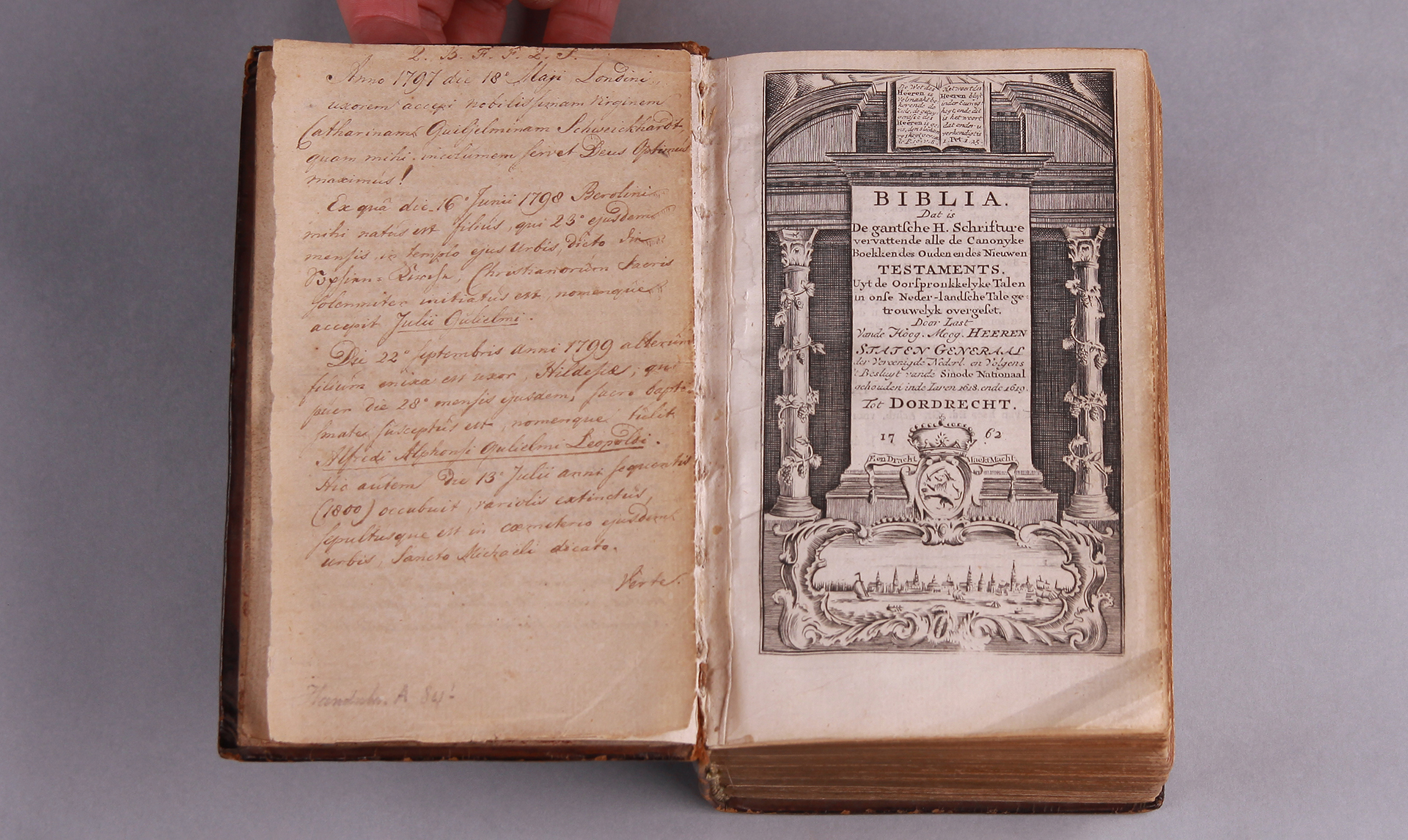

Thus, their relationship became increasingly serious. On 18 May 1797, Bilderdijk noted in his Bible (which is kept in the Leiden University Libraries): ‘Anno 1797 die 18º Maji Londini, uxorem accepi nobilissimam virginem Catharinam Guiljelminam Schweickhardt, quam mihi incolumem servet Deus Optimus Maximus!’ (‘In the year 1797 on the 18th of May, in London, I took as my wife the very noble virgin Catharina Wilhelmina Schweickhardt, whom the Good Lord may protect and preserve for me.’) In his eyes, she now was Mrs Bilderdijk, although an official marriage certificate has never been found. In 1797, Bilderdijk travelled back to Germany; she followed him some time later. As he was still married, they could not live together. Therefore, they continued to write to each other in English, the language that reminded them both of the happy days when they met in London. It was only in 1802, after Bilderdijk divorced his first wife, that they moved in together, and their correspondence ended.

_________

Further reading

About Bilderdijk’s life:

Rick Honings & Peter van Zonneveld, De gefnuikte arend. Het leven van Willem Bilderdijk. Amsterdam 2013.

About the Leiden Bilderdijk collection:

Rick Honings & Gert-Jan Johannes (red.), Een sublieme nalatenschap. De erfenis van Willem Bilderdijk. Leiden 2020.

Online Bilderdijk Room in the Leiden Academy Building

Rick Honings' personal website, with more of his Bilderdijk-related works: www.rickhonings.nl

Become a member of the Leiden Workgroup Bilderdijk: https://www.willembilderdijk.nl