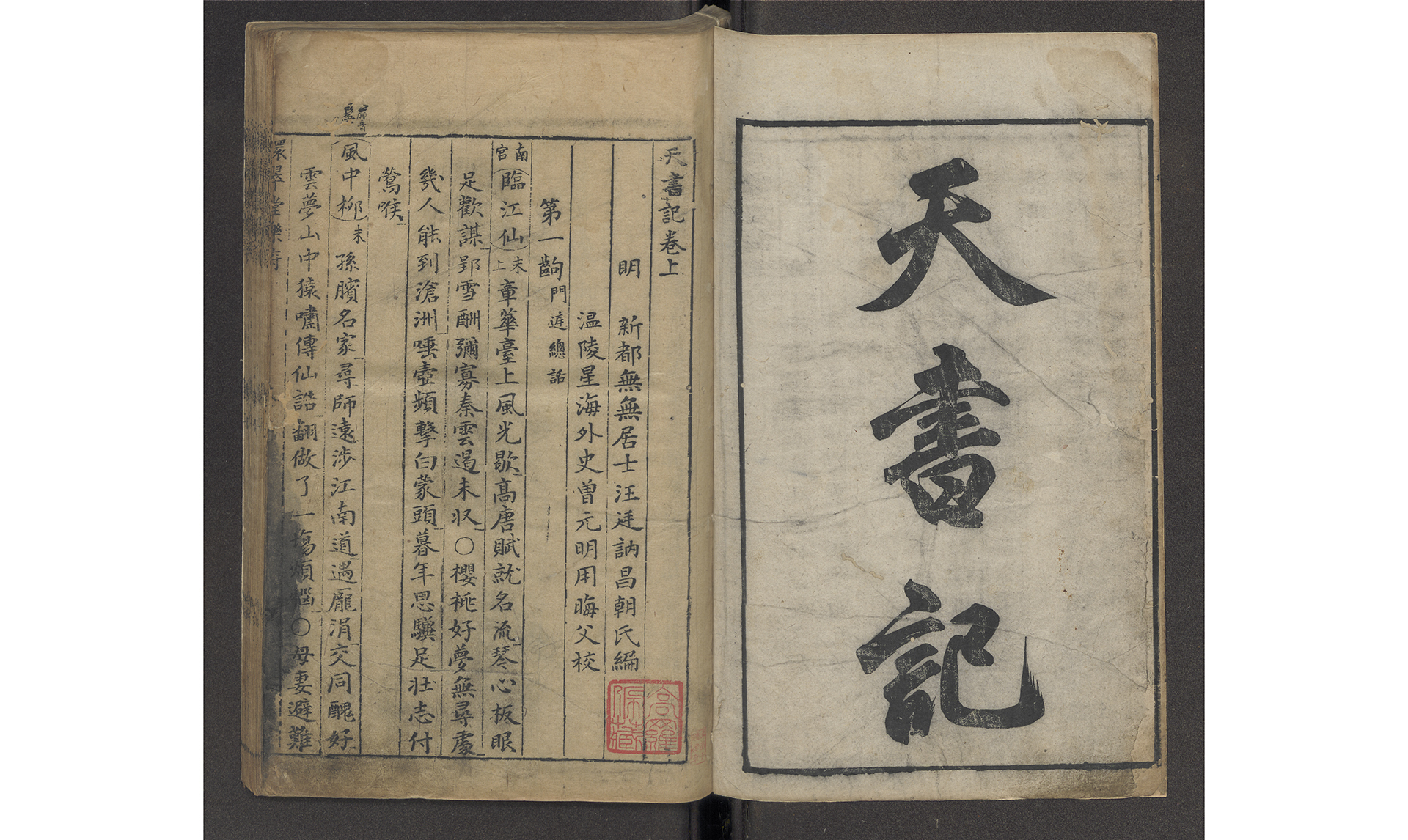

A unique copy of a Yuan dynasty play from the Van Gulik Collection

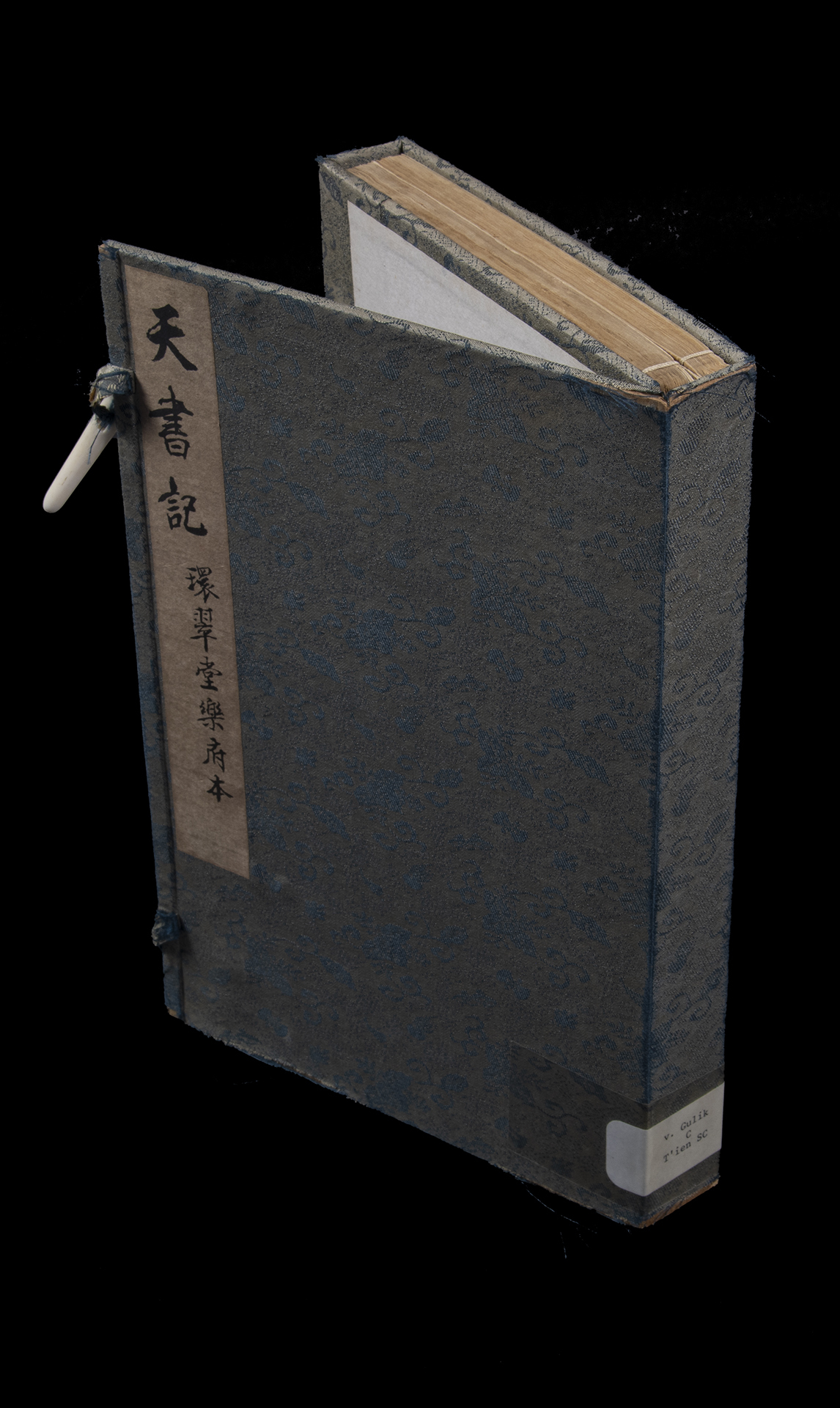

The only surviving copy of a Chinese northern drama published by Wang Tingne: "Record of the Celestial Book" is held in the Asian Library Van Gulik Collection.

The period of the fourth and third century BCE in China is known as the Warring States era. Seven kingdoms fought for supremacy until Qin, from its basis in modern Shaanxi, in 221 BCE unified the Chinese world and the king of Qin declared himself the First Emperor. The fortune of war, however, was not only determined by the strategies of states but also by the personal vendettas of generals and advisers, such as the animosity between Pang Juan 龐涓 (385-342 BCE) from Wei (modern Henan) and Sun Pin 孫臏 (d. 316 BCE) from Qi (modern Shandong) as narrated by Sima Qian 司馬遷 (d. 86 BCE) in his Records of the Historian (Shiji 史記).

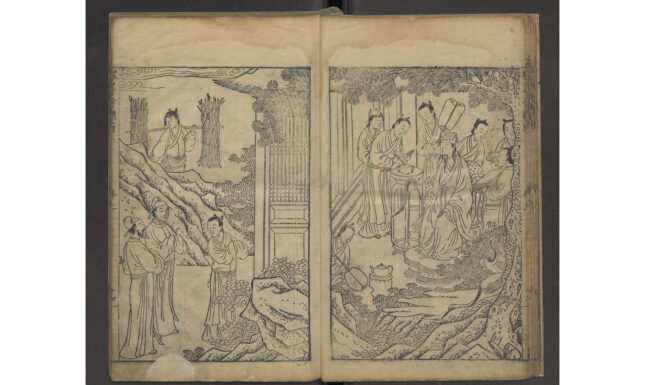

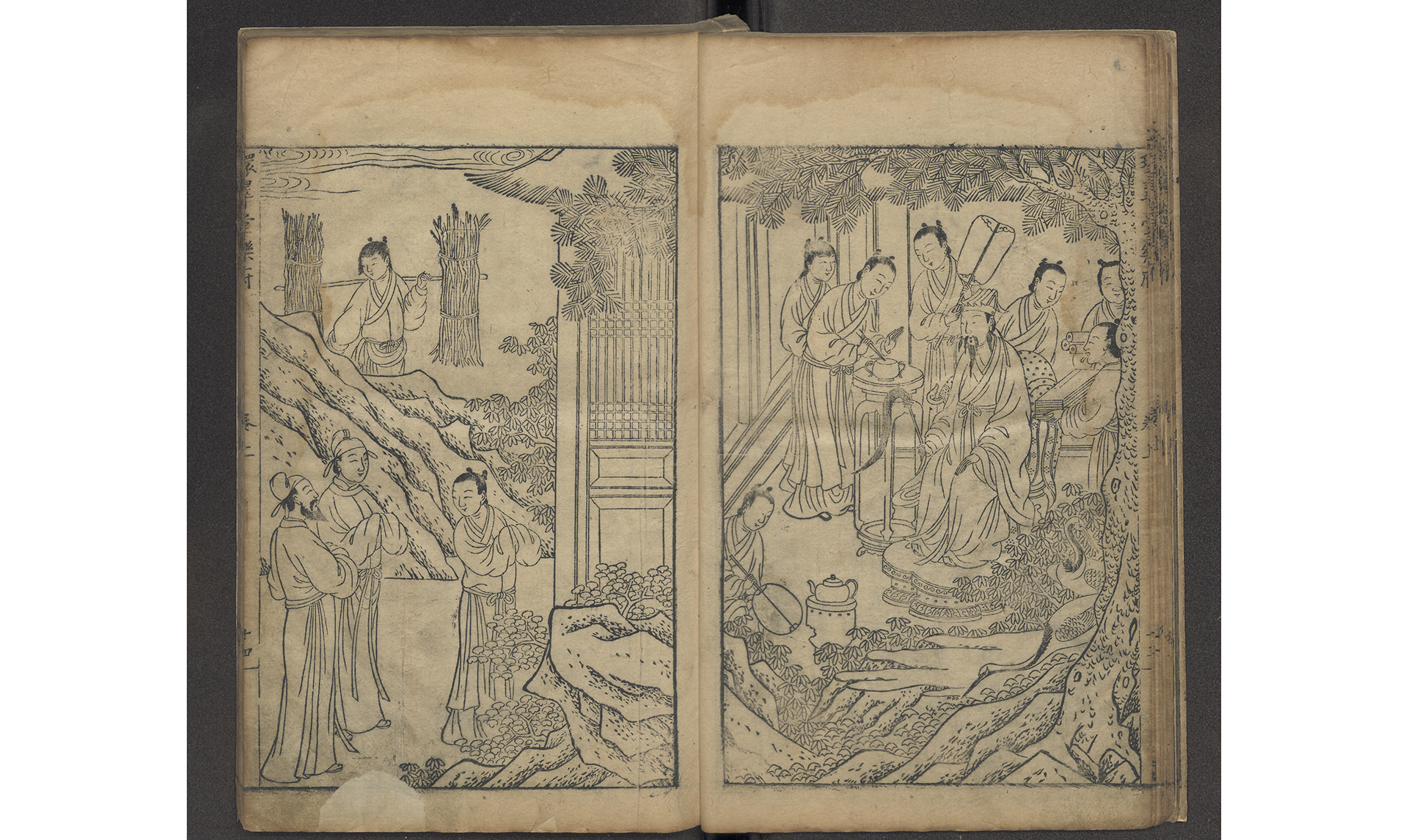

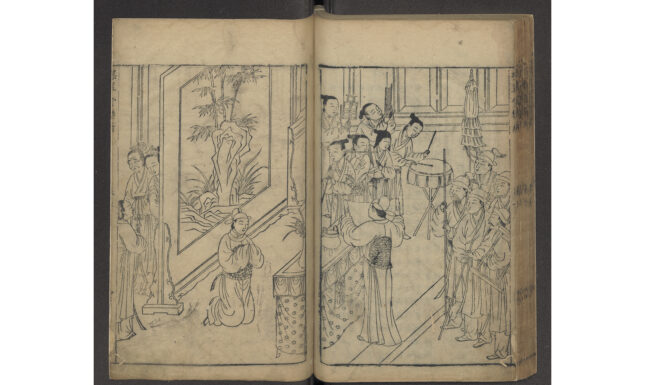

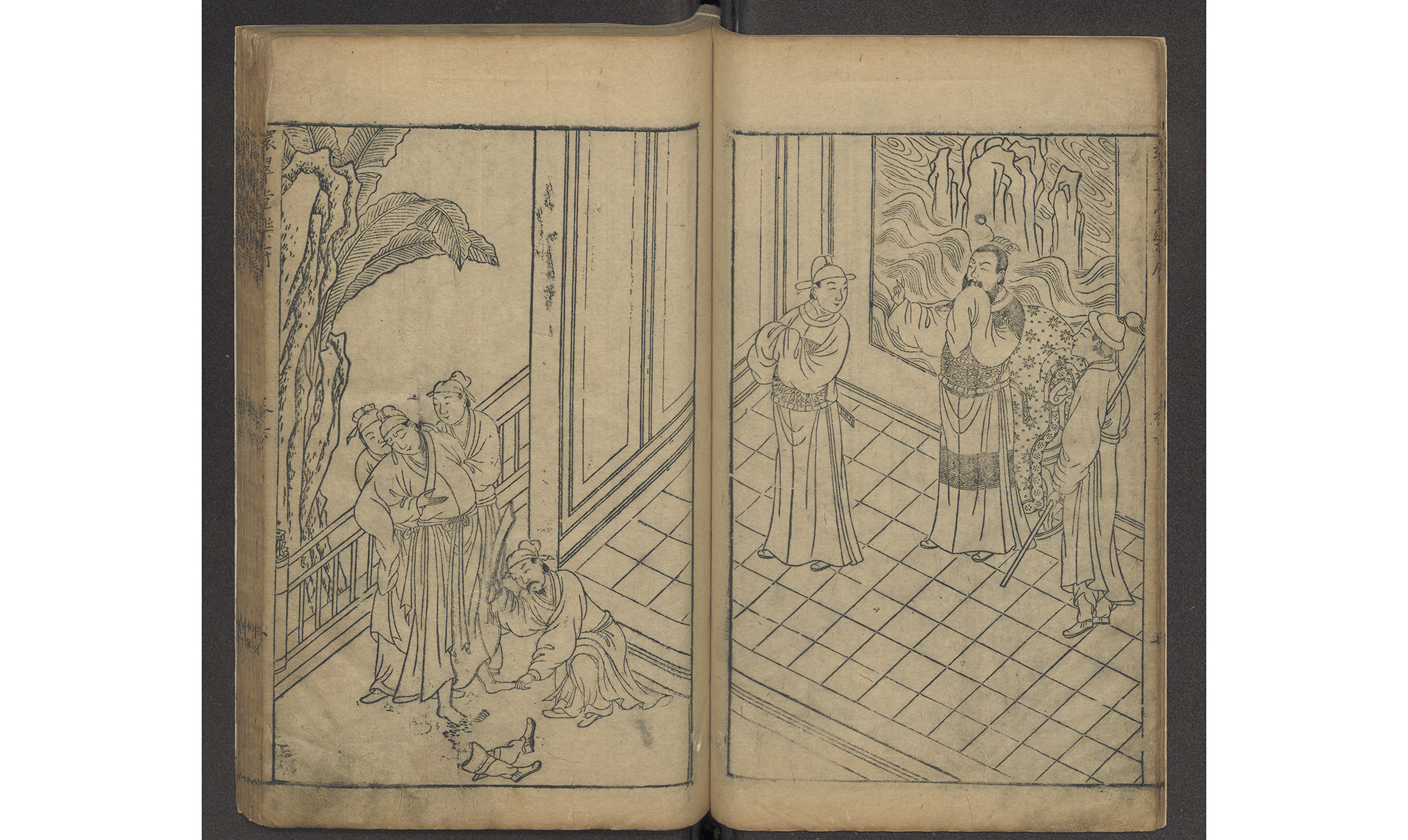

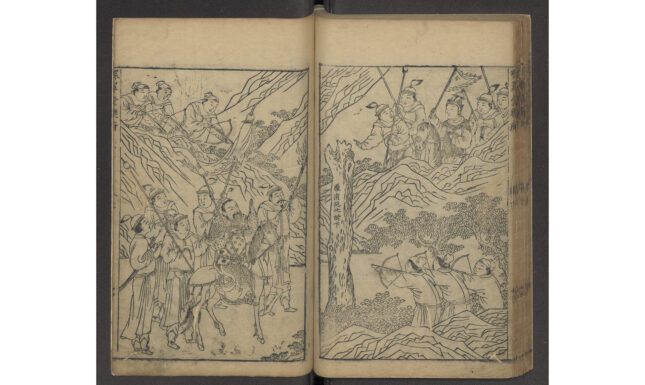

The tale of Pang Juan and Sun Bin was greatly embellished in later ages. The two men started as bosom friends who both studied with the mysterious Master of Ghost Valley (Guiguzi 鬼谷子). Pang Juan was the first to leave his teacher. Once he had achieved a high position as military advisor of the king of Wei, he invited Sun Bin to join him. But admiration turned to envy and jealousy when Pang Juan discovered that Sun Bin, who had received a celestial book of military strategy, might well replace him with his greater abilities. Pang Juan led the king to believe that Sun Bin planned to kill him, and when the king thereupon ordered Sun Bin’s execution, Pang Juan intervened to save his life—but Sun Bin still was tattooed as a criminal and his kneecaps were amputated. Housed in the almshouse Sun Bin feigned madness and was subjected to untold humiliations, while Pang Juan pressured him to provide him with a copy of his celestial book. Eventually, Sun Bin’s compatriots managed to free him and bring him back to Qi, and when Qi attacked Wei, Sun Bin’s superior planning left Pang Juan in such straits that he committed suicide at the precise spot Sun Bin had predicted. A vernacular version of this tale circulated as early as the fourteenth century, and a sixteenth-century novel on this topic remained popular to this very day.

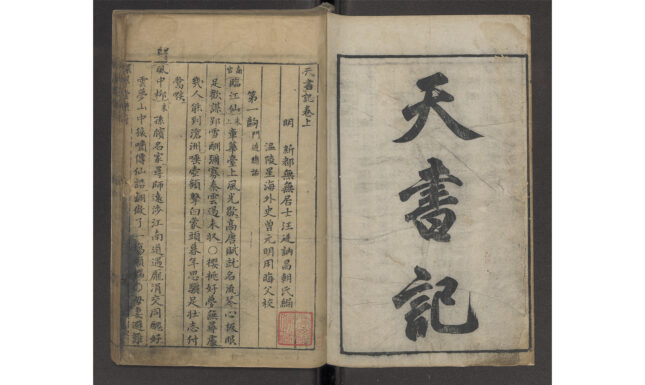

Such a story of betrayal and revenge cried out to be adapted for the stage. An anonymous four-act northern drama survived, from the Yuan dynasty (1260-1368). Southern drama from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) preferred much longer versions in dozens of scenes that allowed for more elaboration and the development of the parts of the minor characters. In these southern adaptations, the story became known as Record of the Celestial Book (Tianshu ji 天書記). The only version of such a play that was known to modern Chinese scholars of traditional theater was Chen Xinqing’s 陳藎卿 Revised Version of Record of the Celestial Book (Chongding Tianshu ji 重訂天書記), which had been printed by wealthy salt-merchant and official Wang Tingne 汪廷訥 (1573-1619), who was also known as a mediocre playwright and publisher of fine books. Drama critics of the early seventeenth century compared this Revised Version positively to an earlier version that they credited to Wang Tingne himself, but drama scholars of the twentieth century had no access to this original Record of the Celestial Book and could only speculate about its content.

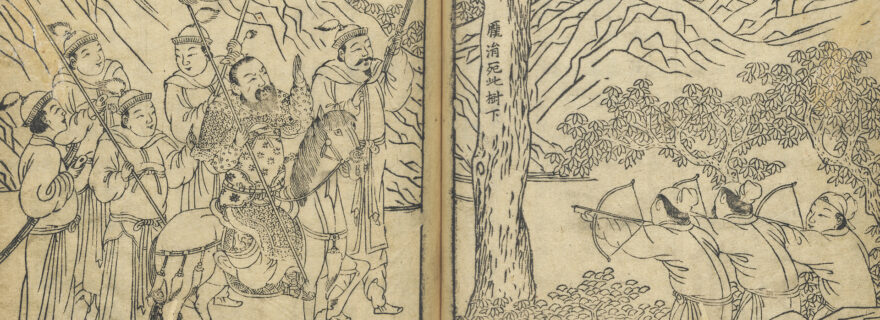

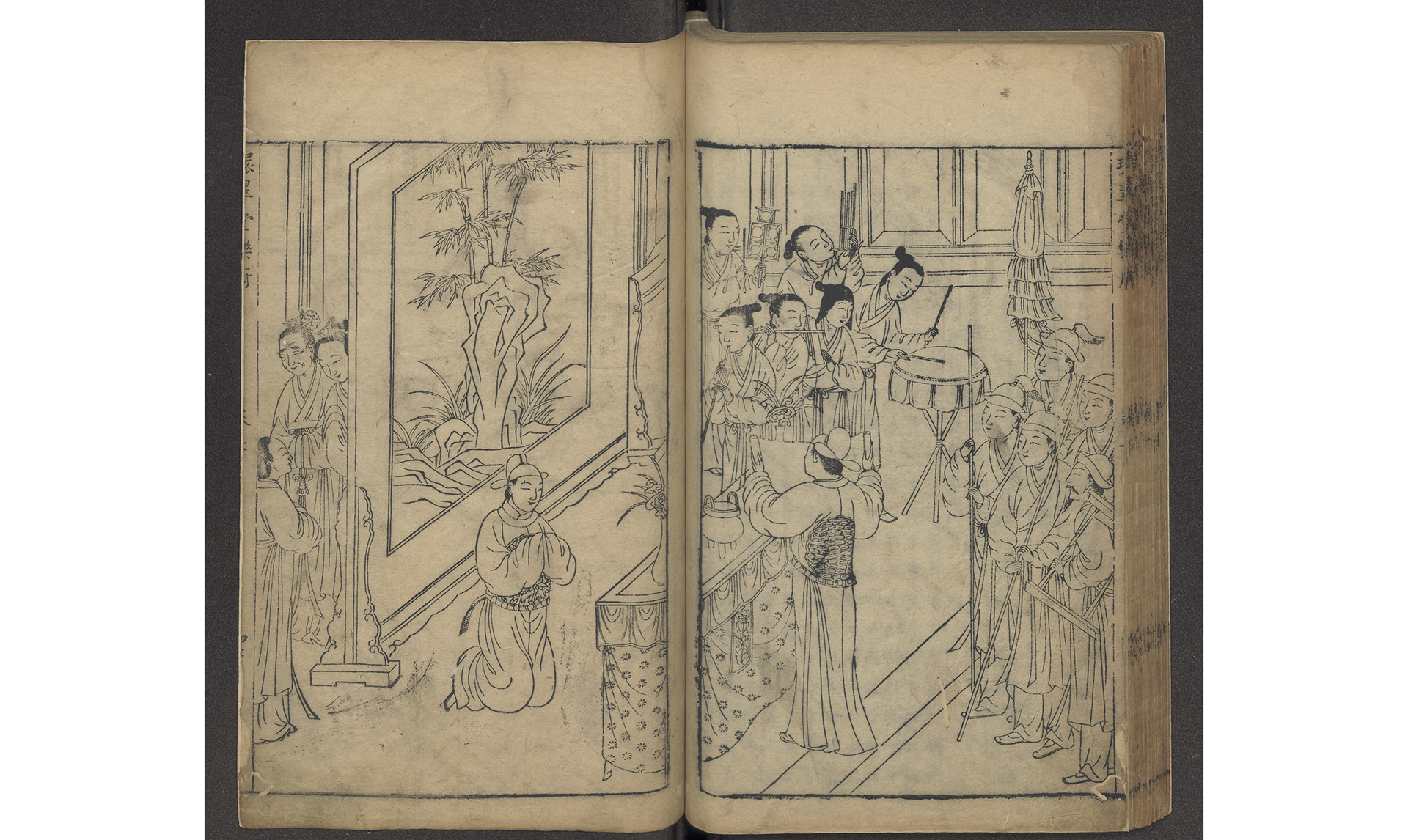

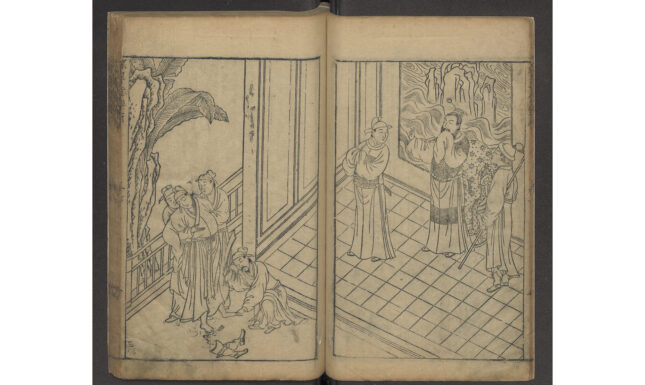

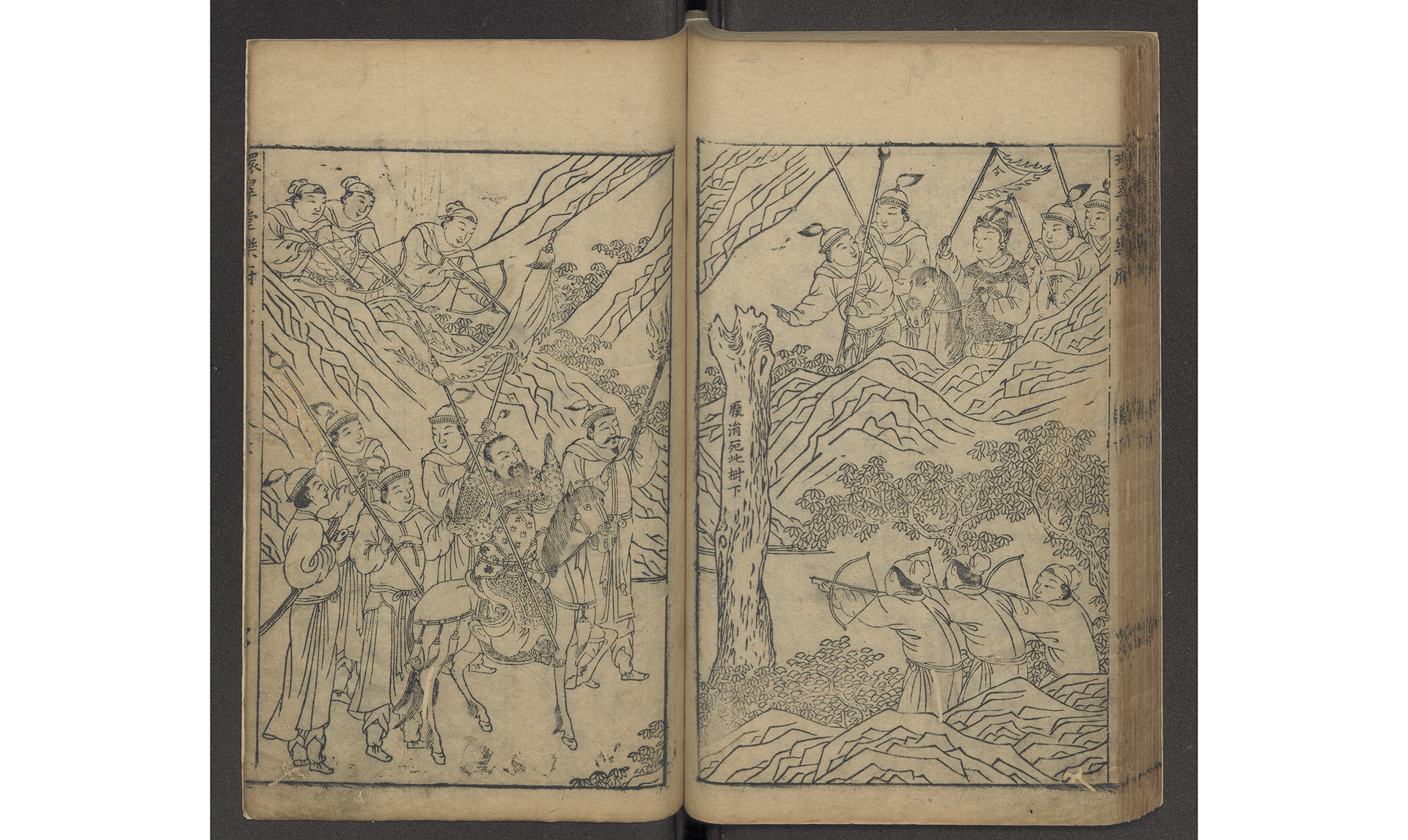

The copy of Record of the Celestial Book in the Asian Library of Leiden University Libraries is the only known preserved copy of Wang Tingne’s play on the tale of Pang Juan and Sun Pin. It entered the library of the Sinological Institute of Leiden University as part of the collection of the famous Dutch sinologist, diplomat and author Robert Hans van Gulik (1910-1967) who probably acquired the book during his second or third posting to Japan. Rich as it is, the Van Gulik Collection is not known for its holdings in Chinese theatre, so what may have spurred Van Gulik to acquire this play? Interestingly, the play relates to Van Gulik’s first and last research project. When Van Gulik, in 1935, had obtained his doctorate and left for Japan where he had been appointed as a second secretary at the Dutch Legation in Tokyo, he set out on an annotated translation of the Master of Ghost Valley (Guiguzi), an ancient collection of treatises on diplomatic rhetoric credited to the Master of Ghost Valley, but this work was never published, as the manuscript was lost in a bombing of Chongqing during WW II. Van Gulik’s last published monograph was The Gibbon in China, An Essay in Chinese Animal Lore (1967), and in Record of the Celestial Book Sun Bin receives this treasure not from some immortal maiden but from a gibbon, an animal that in the Chinese tradition is often credited with supernatural martial skills. As an aficionado of Chinese woodblock printing, Van Gulik may of course also simply have been captivated by the play’s carefully executed illustrations, one of the Hallmarks of Wang Tingne’s publications.

_____

Further Reading

On Wang Tingne’s activities as a publisher of illustrated books, see Li Lichiang, “Wang Tingne Unveiled through the study of the Late Ming Woodblock-Printed Book Renjing yangqiu,” Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême Orient 95 no. 1 (2008), 291-320.

About the author

Prof. Wilt L. Idema taught Chinese Literature at Leiden (1970-1999) and Harvard (1999-2013). His research has mostly focused on late-imperial vernacular traditions, such as fiction, drama, and ballads.