Bilderdijk’s eyebrows: romantic relic worship in the 19th century

If you look at the original death mask of Willem Bilderdijk (1756-1831), you can still see the bushy eyebrows of the famous Dutch poet. The fact that such a mask was made tells us a lot about Bilderdijk’s status as a celebrity, but is also characteristic of 19th century Romantic relic worship.

In 2019, the Vereniging (Association) ‘Het Bilderdijk-Museum’ decided to give its collection ‘Bilderdijkiana’ (Bilderdijk items) on permanent loan to the Maatschappij der Nederlandse Letterkunde (Society of Dutch Literature) in Leiden, that already owned a lot of Bilderdijkiana. Three known Bilderdijk collectors were Bastiaan Klinkert, Jan Wap and Hendrik Tollens. The collections of Klinkert and Wap ended up at the Maatschappij in Leiden; those of Tollens formed an important basis for the collection of the Vereniging ‘Het Bilderdijk-Museum’ in Amsterdam. The Leiden and Amsterdam collections are now fraternally united in the city that Bilderdijk characterised as the ‘Eden of the World’. Leiden was the only place where he had ever been happy. Because of the collection’s transfer, Leiden now houses the largest Bilderdijk collection in the world. It consists of old prints, manuscripts, letters and works of art. Together, they form a fundgrube for research.

The paintings of the Vereniging could not be accommodated in the University Library. Fortunately, a solution now has been found. A period room in the Leiden Academy Building, the ‘Green room’, has now become the ‘Bilderdijkkamer’ (Bilderdijk-room). Most of the paintings hang here, while a beautiful display case houses several special objects, such as his walking stick and a letter opener.

Bilderdijk became famous during the Romantic era; he had the eccentric image of a suffering, poverty-stricken but also a divinely inspired poet, who lived in discontent with the world around him and who was desperate for death. At a time in which modern media did not yet exist, he conveyed that image, except for in his poetry, mainly through portraits. No other Dutch poet of his time was depicted as often as he was. About fifty portraits of Bilderdijk are known: both small and large, of famous and unknown painters. Based on many of those images, engravings and lithographs were made, that were for sale for a small amount.

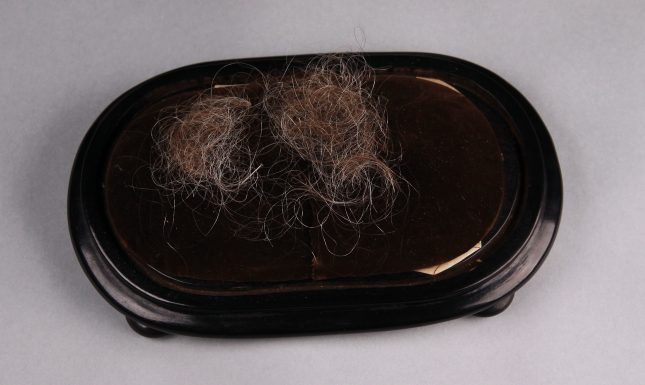

Under the influence of Romanticism, not only did the image of the poet become more important. Something also changed on the side of the audience. Because the artist is seen as a genius, the objects borrowed from his body, touched by him or otherwise reminiscent of him, take on almost religious status. In the nineteenth century, celebrity relic collecting became very popular. Remains of the author's dead body were a way for fans to stay in touch with the dead genius and were seen as remains of a unique personality.

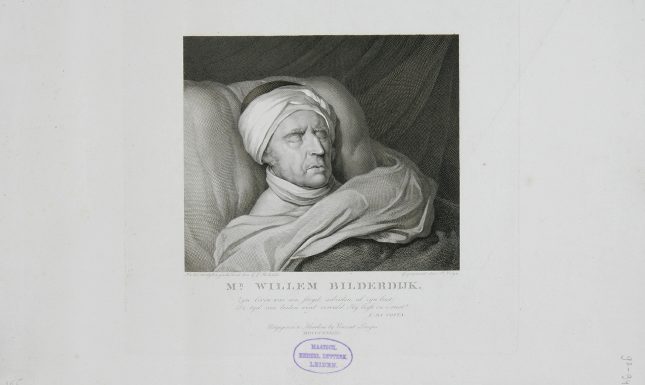

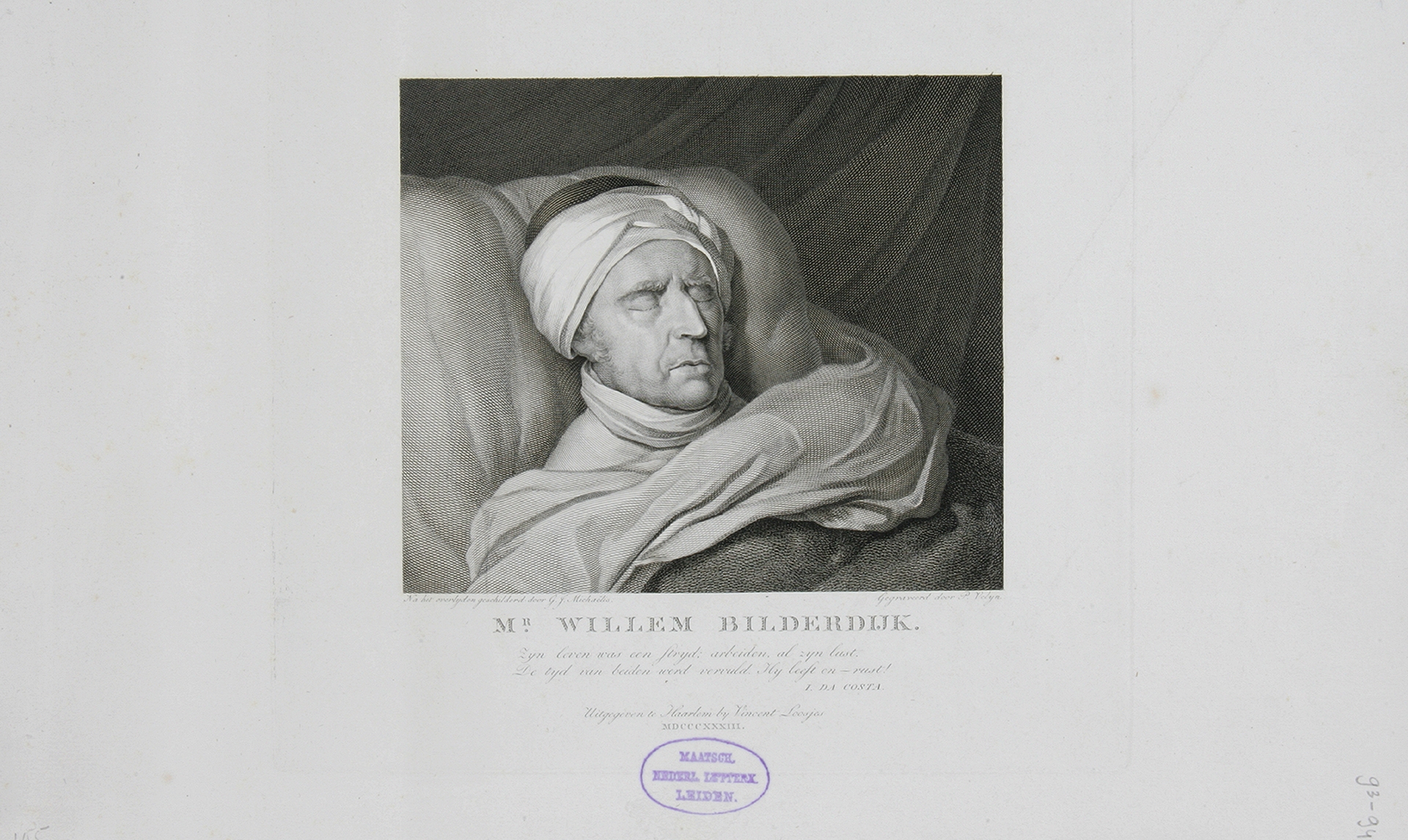

That is why so many romantic relics have been preserved in the Leiden Bilderdijk collection. When Bilderdijk passed away in Haarlem on December 18, 1831, a death portrait was immediately made by Gerrit Jan Michaëlis, which now hangs in the Bilderdijk-room. Based on this painting, engraver Philippus Velijn made a print, which was for sale in many bookstores. Michaëlis’ portrait also inspired the bust made by the Flemish sculptor Louis Royer in 1832, of which smaller versions were subsequently produced.

Further, strands of Bilderdijk’s hair were cut off after his death. In the nineteenth century, hair was often kept in memory of a deceased, but the extent to which this happened with authors in the Romantic era is special. One could easily make a wig from Bilderdijk’s preserved hair.

Another masterpiece and a highlight of the romantic cult of relics is Bilderdijk’s death mask. After his death, Amsterdam-based sculptor Antonio Boggia came to Haarlem to make a plaster cast of Bilderdijk's face. When the cast was released, parts of the eyebrows were accidentally pulled out, which can still be seen in the mask. It says a lot about Bilderdijk’s status that it was the first time that a death mask of a famous person was made in the Netherlands. The House of Orange would not follow until 1849, after the death of King Willem II.

Bilderdijk’s right hand, the hand with which he wrote his verses, was also immortalised in plaster. Four copies are kept in the collection. One of them reads: ‘Cor sapientis in dextera ejus’ (The heart of a sage is in his right hand). Such artefacts can be seen as expressions of the international romantic cult of relics around poets in the first half of the nineteenth century.

On 18 December 2020 Leiden University Libraries will present an online programme around the Bilderdijk-collection. This programme will be available via livestream on the UBL website. The programme will be presented in Dutch.

Rick Honings recently co-edited a book about the Bilderdijk-collection at Leiden University Libraries: Rick Honings & Gert-Jan Johannes (red.), Een sublieme nalatenschap. De erfenis van Willem Bilderdijk (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2020).