Following Ganesha’s footsteps through the Leiden Special Collections

Follow Ganesha in his many forms through the Asian Special Collections at Leiden University Library.

Ganesha is a god. One that loves travelling on a large rat. Buddha-like is his belly, and one of his tusks is broken – yes, he has a sweet tooth, but this tusk broke in violent action [various versions available]. Ganesha has an enormous work package: he is the god of all beginnings, of knowledge and wisdom, success and good luck, and he is the remover of all obstacles. He is also the patron of all intellectuals, bankers, scribes, authors - and of all library folks! But most strikingly, he is the god with the head of an elephant.

Before following Ganesha’s traces in the UBL/KITLV/I.Kern collections, here a short biographical note:

His father is god Shiva, his mother the goddess Parvati. Longing for a guard entirely loyal to her (and not to Shiva), Parvati had formed a boy from clay. She had deemed this necessary, as Shiva had made it a habit to visit her whenever she was taking a bath. Nandi, the bull, had turned out to be too loyal to Shiva, he would not protect her but let Shiva pass unimpeded. The little boy Ganesha, however, not recognizing the god Shiva, could resist successfully. Shiva got furious and finally cut off Ganesha’s head. Parvati was not amused (understandably so!) and threatened to destroy the entire creation. That alarmed Brahma, the Creator, and that again made Shiva nervous. So he quickly went to search for a substitute head for the boy in order to bring him back to life. The first head available was one of an elephant. It was placed onto Ganesha’s body - one tusk, as mentioned above, broken during the decapitation. When Ganesha finally was back among the living, Shiva acknowledged him as his very own son to be worshipped before all other gods.

Whoever wishes to learn more about the deeper philosophical meaning of this story or other aspects of Ganesha, will easily find a multiplicity of sources via the UB-Catalogue: Type in Ganesha in the search field and you will get c. 13,504 results, 13,225 of which can be accessed online.

In the following, I will focus on a small selection of items from the Special Collection (I thank Prof. Peter Bisschop and Dr Daniele Cuneo for sharing their expert knowledge during the preparation for a Sanskrit pop up exhibition in 2015):

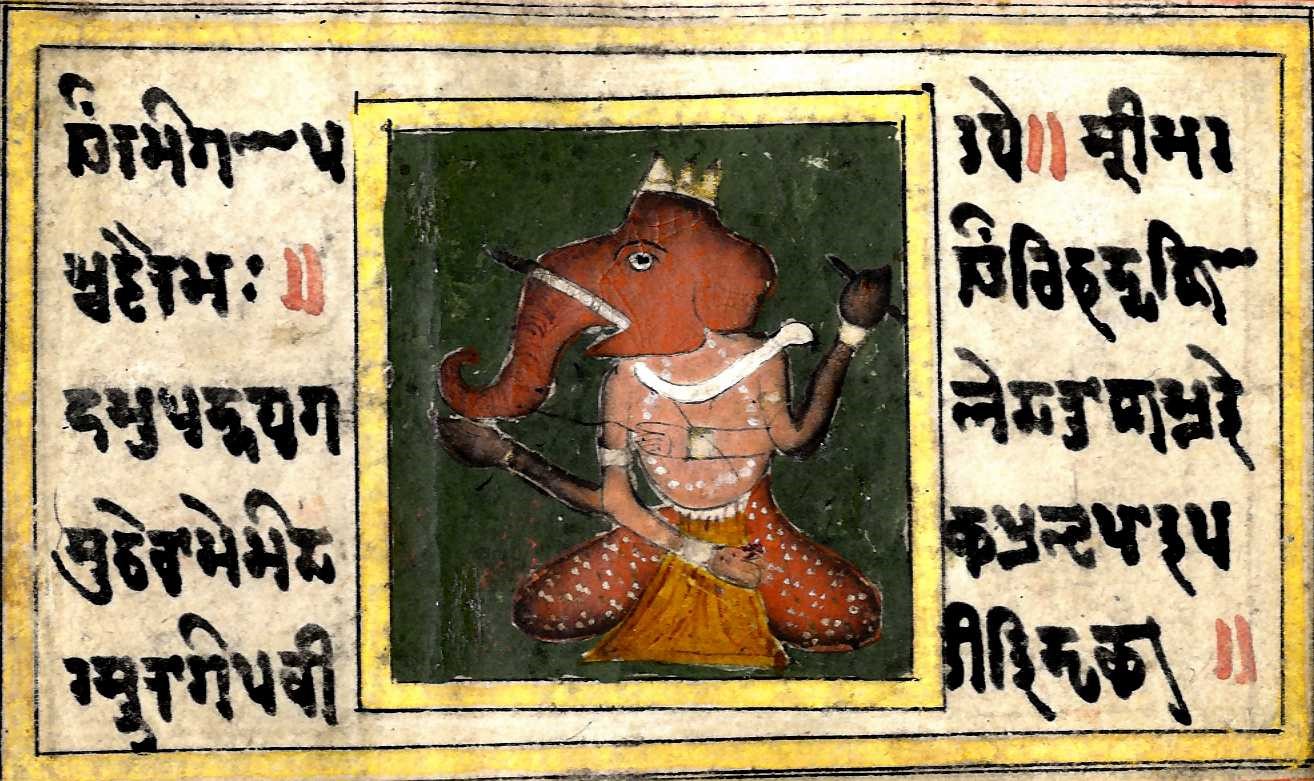

[Or. 25.464, Northern India]

This small 19th-century manuscript with a cover made of cloth contains several devotional texts, among them the Śivaśaṅkarastotra and Gaṇapatistotra, a prayer to Ganesha. Remarkably, Ganesha does not appear at the opening of this text. Possibly the prayer was deemed powerful enough to remove all possible obstacles. Ganesha makes his appearance forty pages later in form of a polychrome miniature drawing. The manuscript is in Śāradā script (on paper), and numerous annotations by various hands document it as being an object of careful study in the past.

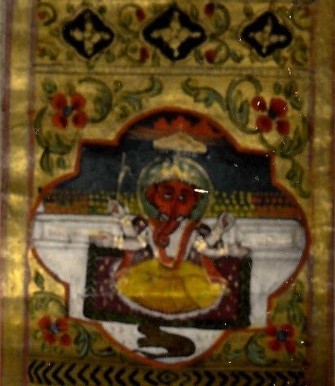

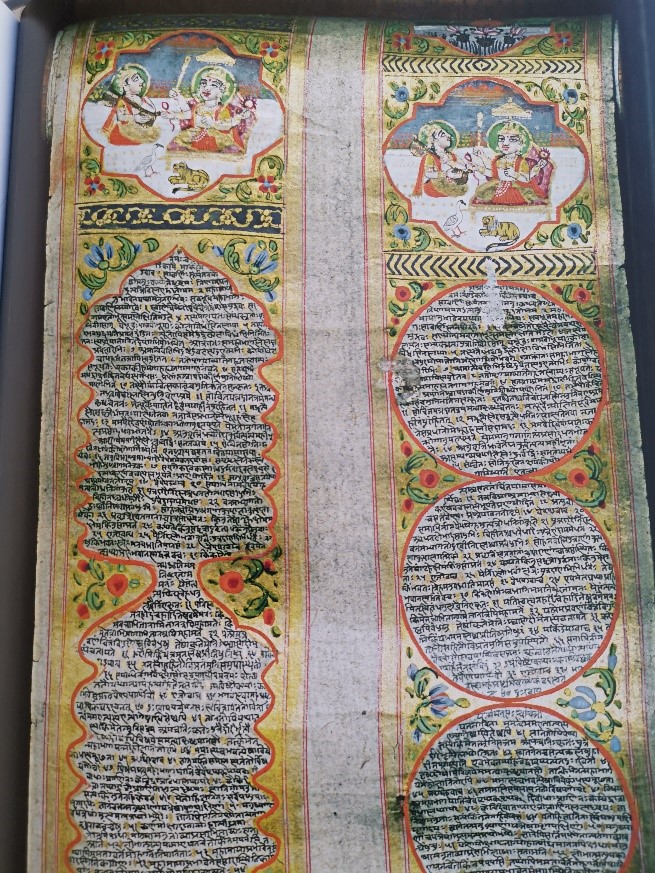

[Or. 18.301, Northern India, c .1800]

This scroll manuscript on paper in a wooden box opens with a twin-miniature image of Ganesha. It is one of the most beautiful Sanskrit manuscripts in the Leiden collection but requires a looking glass to decipher its minuscule letters. The Devīmāhātmyam makes part of the Mārkaṇḍeyapurāṇa and glorifies the great goddess Devi. She is presented as Laksmi, Sarasvati and Durga, the three vital powers of the gods Visnu, Brahma and Siva.

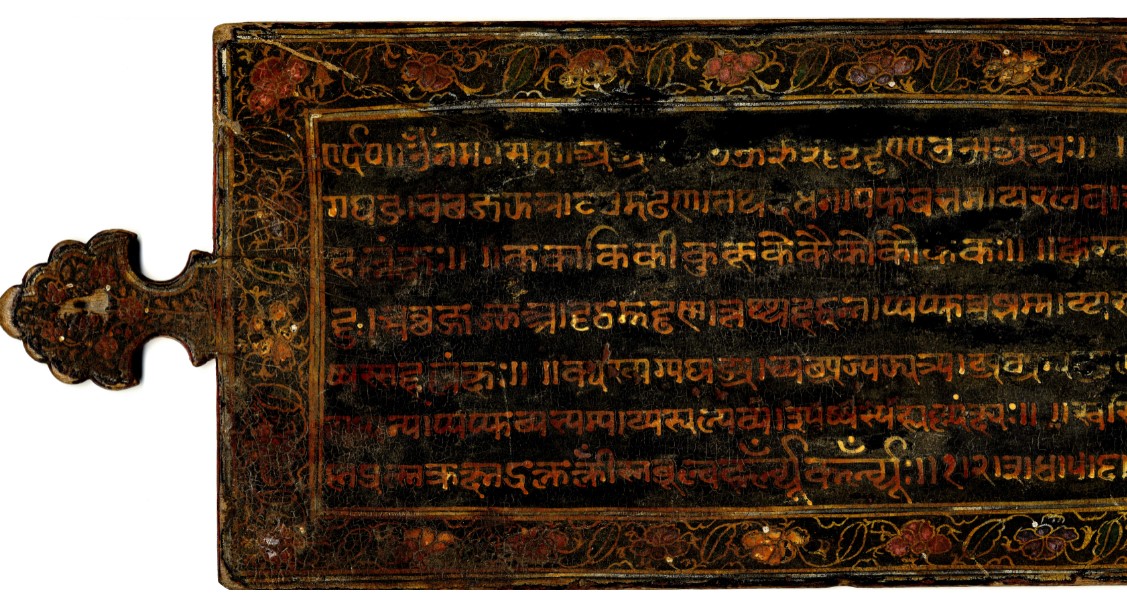

[Or. 27.241]

Its shape might resemble a cutting board, but this wooden board (early 20th century) was meant for Indian pupils to copy the Devanagari script in order to practice and eventually learn it. Boards like this are still in use to date. Verso, Ganesha is sitting on a lotus blossom, safeguarding the learning efforts of the pupils.

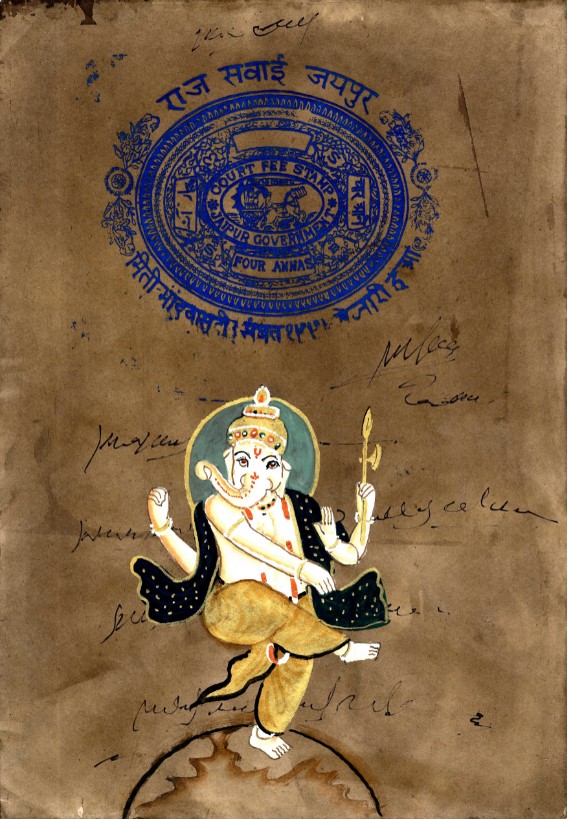

[Or. 27.698]

This drawing, one in a set of five, on (probably fake) pre-stamped “Court Fee” Government office paper of Jaipur (1918-1927) is possibly a mere drawing exercise. Maybe it is the plea for Ganesha’s blessing for a new business activity aiming at naïve tourists. Against his habit, Ganesha is dancing on his left leg.

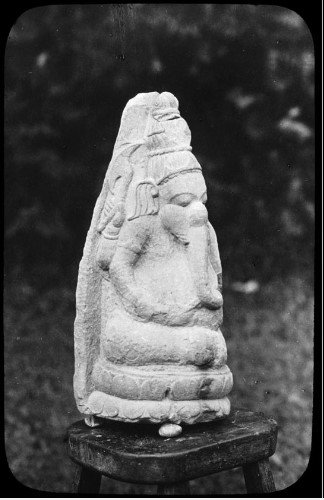

In Indonesia Ganesha rarely dances but is usually depicted in a sitting position, as seen on the 19th century photograph taken by I. van Kinsbergen of a statue from the Parikesit temple in Central Java.

KITLV 87719

Ganesha is less obviously present in Indonesia than in Indian cultures, but he is well-known nonetheless. Educational centres and Art galleries often bear his name, and even a movie film distributor does so. Some people believe that putting Ganesha on the 20.000 Rp bill helped to stabilize the Indonesian currency during crisis.

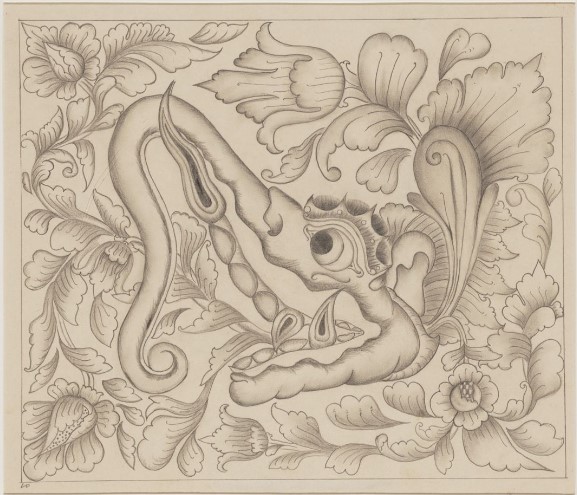

[KITLV 48N35]

by a Balinese schoolboy (age 7)

[KITLV 49A1]

by a Balinese schoolboy (12-15), c. 1967

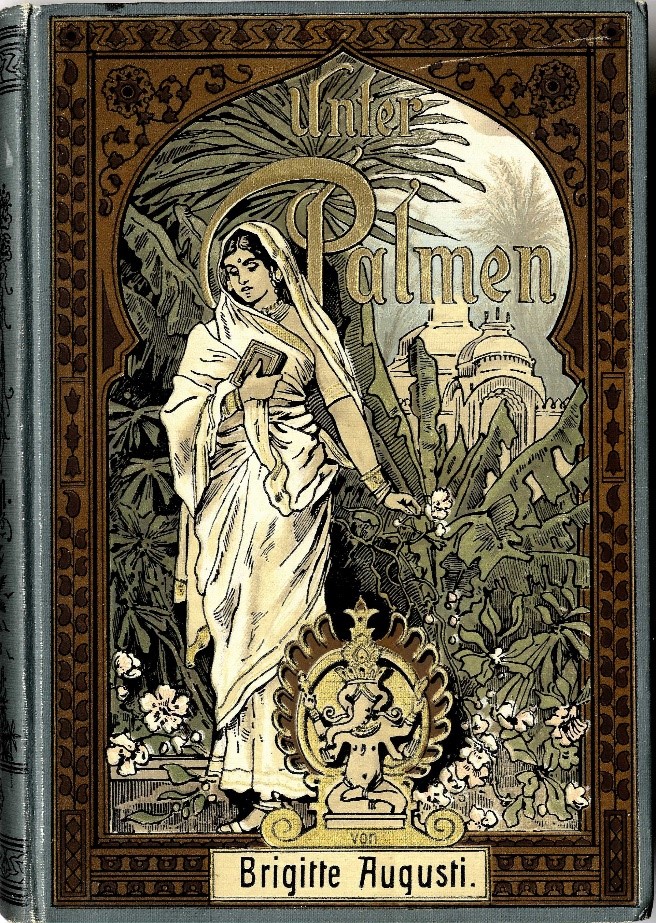

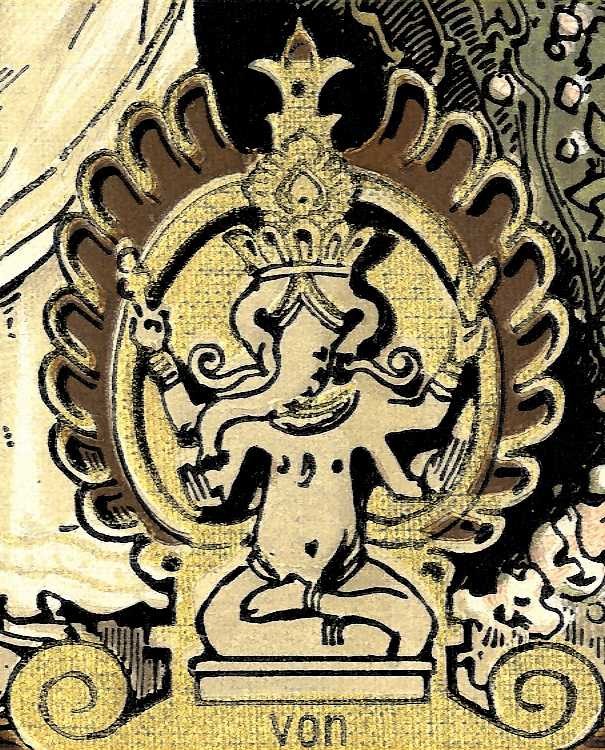

Concluding this ‘godly’ library tour, we return to the book world and a beautiful cover adorned by Ganesha. It may be doubted that Hindu god Ganesha would ever want to bless the missionary work of the Europeans in India or elsewhere.

Brigitte Augusti, Unter Palmen. Schilderungen aus dem Leben und der Missionsarbeit der Europäer in Ostindien. Leipzig: Jugendschriftenverlag von Dr. Max Gehlen [no year]. 5e Aufl.

I.KERN GD 03 179

This blog post is an extended version of a short article published in the Newsletter Vrienden van het Instituut Kern, May 2019.