Political propositions: Willem Bilderdijk’s legal dissertation

Many recognise Willem Bilderdijk as one of the greatest poets in Dutch literary history, but only few know that he was a rather famous lawyer, all thanks to his education in Leiden. Letters, lecture notes and other documents provide insight into his time as a law student at Leiden University.

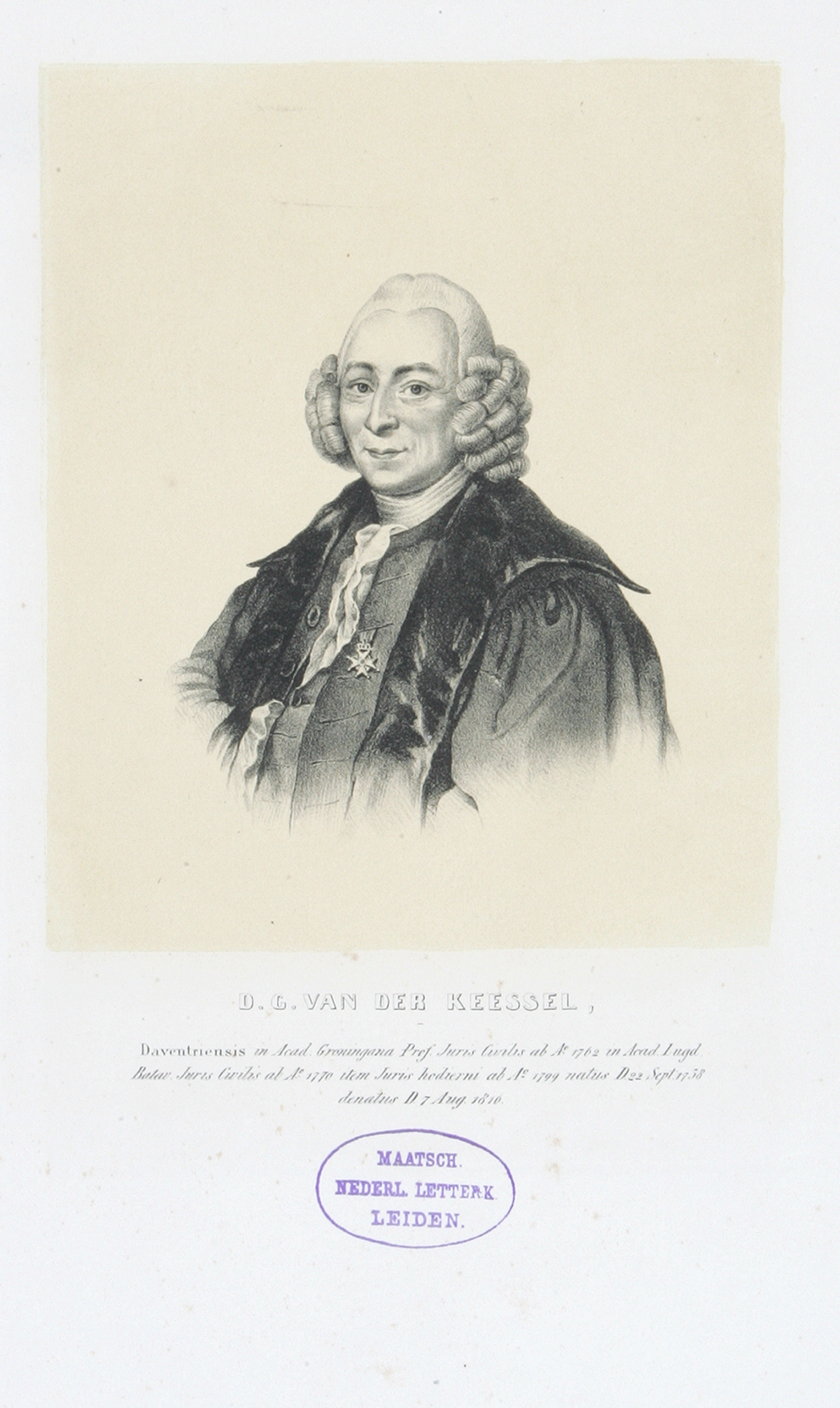

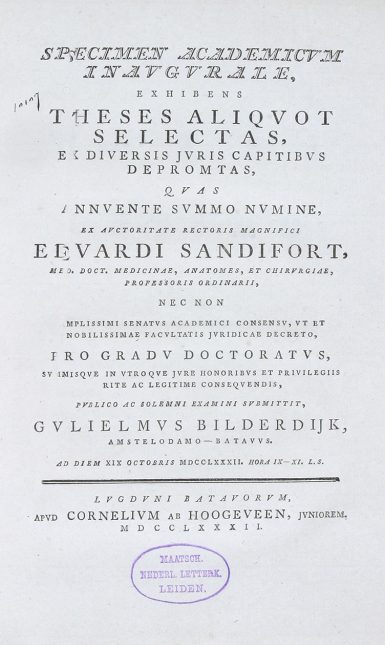

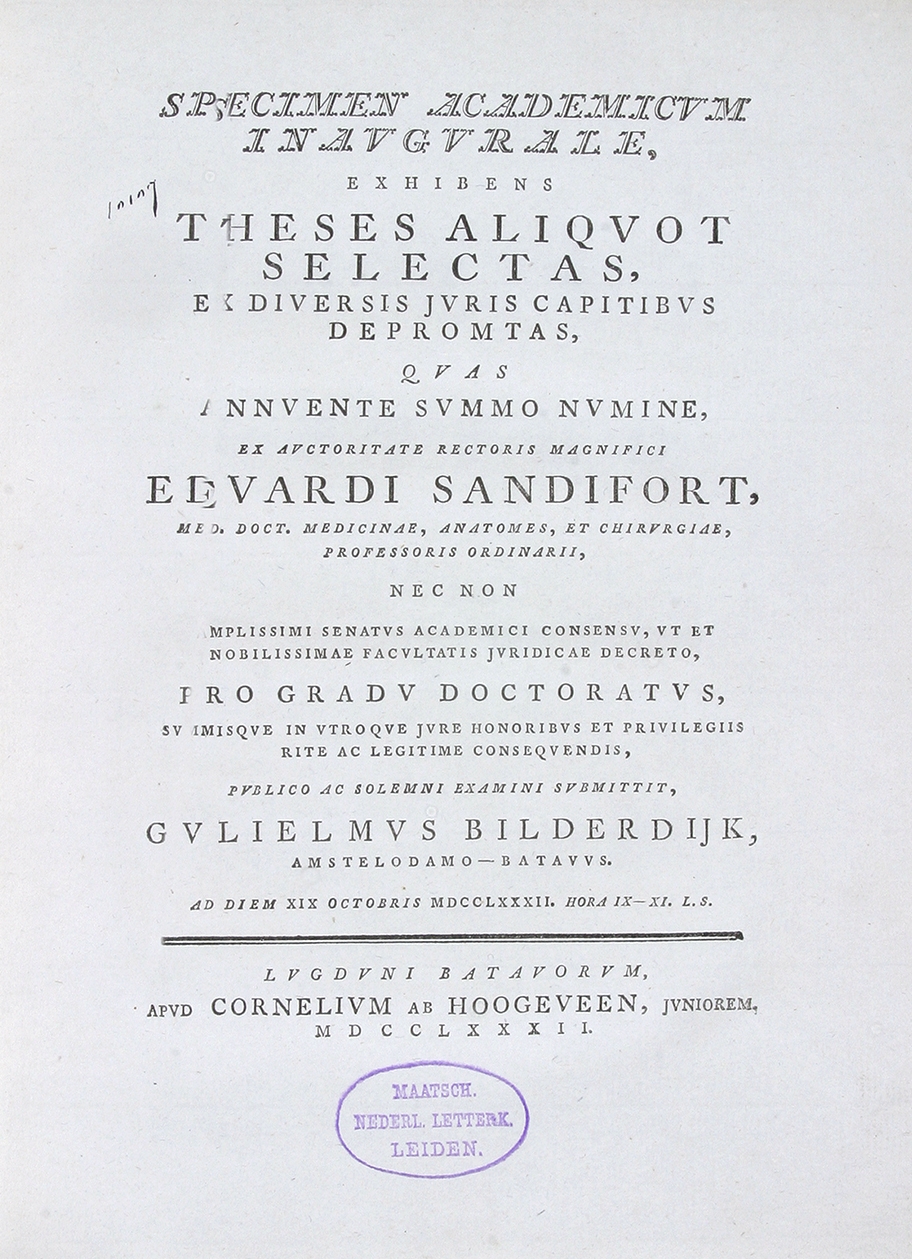

Proposition XXXIX: ‘Julius Caesar has been killed unfairly and unjustly.’ God had given Caesar absolute power and his assassination was therefore contrary to Gods will. That could be what this statement means, given its author. Willem Bilderdijk did not beat around the bush when, on 19 October 1782, he defended his propositions in order to obtain his legal doctorate in Leiden. The title of the collection of theses, obviously written in Latin, is Specimen academicum inaugurale, exhibens theses aliquot selectas, ex diversis juris capitibus depromtas and thus concerns ‘a selection of some theses drawn from various chapters of the law’. Almost everyone will recognise Bilderdijk's name, many will know that he was a poet, but relatively few people know that he was also a rather famous lawyer in his time. On 19 May 1780, the 24-year-old Bilderdijk, who at that time was already known as a poet, registered as a law student at Leiden University. He would attend lectures there between 1780 and 1782.

Bilderdijk was fascinated by both his studies and Leiden student life. The letters he wrote to his friend Rhijnvis Feith during his period as a law student provide insight into the life of a Leiden law student in the second half of the eighteenth century. 'For the rest,’ Bilderdijk writes to Feith on 27 October, ‘I am a real legal scholar nowadays! I advise, respond, argue, and whatever is more like that, as if I knew quite a bit about it.’ Bilderdijk enjoyed acquiring legal knowledge in a playful way and his talents did not go unnoticed.

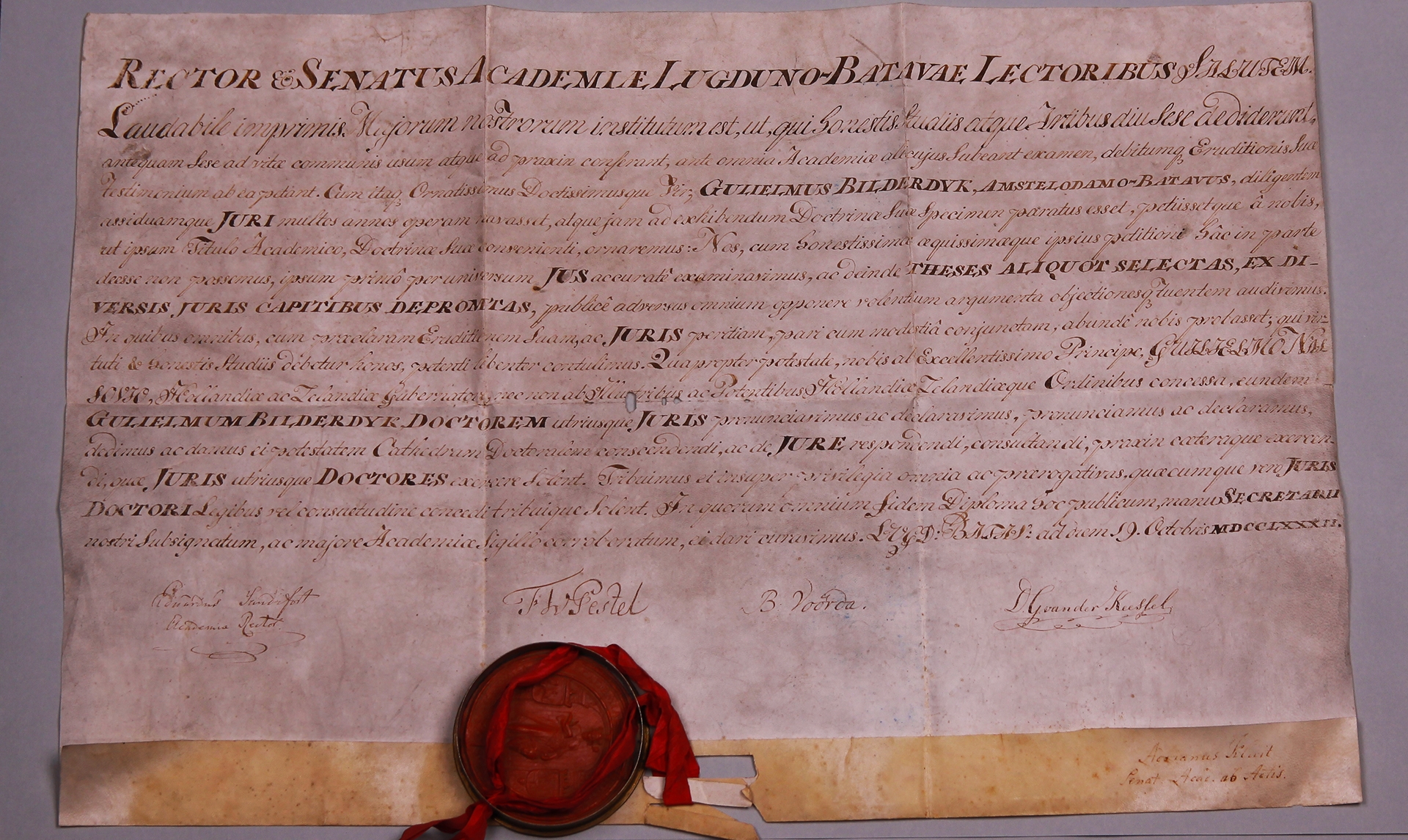

In his second year of study, Bilderdijk is invited by Professor Dionysius Godefridus van der Keessel to attend a so-called ‘privatissimum’: a monthly private meeting with a few fellow students. They gather every Tuesday evening at the professor's home. Privatissum is generally described exactly as by Bilderdijk: as a series of lectures by a professor on a specific subject, at his home. Even now, the privatissimum is still part of the law curriculum at the Leiden faculty, although the lectures no longer take place at the home of professors, but in the Kamerlingh Onnes Building or (currently) even online.

Bilderdijk carefully recorded the privatissimum he attended as a second-year student in the form of a lecture note, which is in the possession of the KNAW; in 1986, Heleen Gall made an edition of it. On the front of the booklet, we can still clearly read 'W. Bilderdijk. Studiosus 1781. Mss. '. In the academic year 1781-1782, Bilderdijk attended the privatissimum on eight Tuesday evenings. During these lectures, legal cases were discussed that probably had to be worked out by the students at home. It concerns ‘Digest exercises’; both the various cases and corresponding solutions are taken from the Digest: the collection of legal texts drawn up by the Roman emperor Justinian around 530 AD. This is not surprising, since Van der Keessel mainly taught courses in Roman law.

The existence of a privatissimum is not the only similarity between Bilderdijk's life as a law student in Leiden and that of today's legal students. Bilderdijk also pulled some all-nighters:

Student life in Leiden kept young Bilderdijk busy all day long. Sleeping was no longer an option: ‘Meanwhile, all these niceties drag away so much time that I can't yawn: eating, drinking, and sleeping (or rather, being in bed) are things that are rarities for me today.’ However, this commotion does not last very long. His father allowed Bilderdijk only two years to study law, which was not uncommon at the time.

On January 27, 1782, Bilderdijk wrote to Feith:

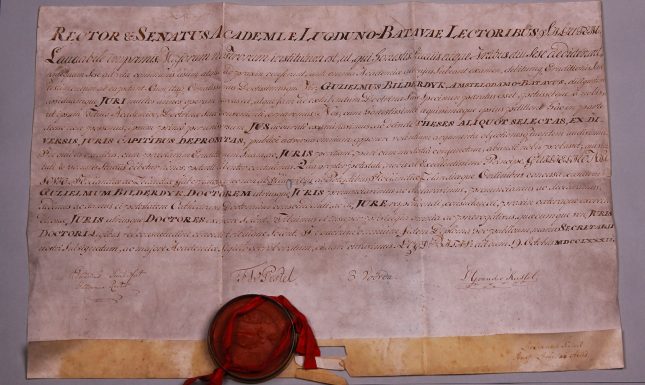

On October 19, 1782, Willem Bilderdijk obtained his doctorate (cum laude) by defending his 105 theses, which he dedicated to his father. The defense took place between 1 and 3 o'clock. That afternoon, very diverse topics were discussed. The 105 statements include criminal judgments, statements about war, comments about public law and comments about private law. Bilderdijk also occasionally explicitly enters a dialogue with great (legal) scholars, such as Plato (proposition LXI), Montesquieu (XXII), Grotius (VII and XXI) and Van Bijnkershoek (XLVIII). It is, among other things, in the thesis in which the latter scholar occurs that Bilderdijk also devotes a few words to the Union of Utrecht.

In a letter to Feith, Bilderdijk got into more detail about the various propositions he had defended two days earlier. He himself described them as provocative, or, in his own words: 'heterodox'. ‘Think,’ he wrote to his friend, ‘whether one needs to have some courage to swim against the tide like this and to hang the knife (as the saying goes) at a public defence.’

Bilderdijk’s propositions vary from very general legal-social insights - compare proposition IX: ‘Nullum bellum est licitum nisi necessarium’ (‘No war is justified as long as it is not necessary') - to remarks about specific legal acts - compare proposition LI: ‘Ubi poena lege constituta est factum regulariter valet’ ('Where a punishment has been pronounced according to the law, legally, the fact applies in general').

Some of the statements are downright political. Bilderdijk was an outspoken Orangist and this was reflected in his dissertation. In this context, it is remarkable that it is precisely the well-known Patriot publisher Cornelis van Hoogeveen junior, who published Bilderdijk's propositions. One explanation could be that he was the founder of the Leiden poetry society Art is acquired through labor (Kunst wordt door arbeid verkreegen), where Bilderdijk was known as a talented poet since 1776.

It is proposition XLVI that Bilderdijk himself jokingly calls 'the pinnacle of all heresy' in a letter to his friend Feith. ‘Optimum Libertatis Civicae praesidium in republica nostra consistent in Capite Eminenti’, it says, which means ‘The prince ('Capite Eminenti ') offers the best protection of civil liberties.’ Defending such a thesis in patriotic Leiden can be seen as an act of resistance. The Orangist doctor seems to have emphasised his political preferences once again during the festivities that followed the defence: ‘I gave a rather brilliant promotional meal, during which (quod mireris!) we toasted on ZD Highness!’ Shortly afterwards, Bilderdijk established himself as an Orangist lawyer in The Hague.

Quotations are translated by the author.

About the author: Lotte van den Bosch is a Master's student of Literary Studies and Constitutional and Administrative Law at Leiden University.

Further reading

Bilderdijk, W., Specimen academicum inaugurale, exhibens theses aliquot selectas, ex diversis juris capitibus depromtas. Leiden: Hoogeveen, 1782.

Gall. H.C. (ed.), Willem Bilderdijk en het privatissimum van professor D.G. van der Keessel. Den Haag: Jongbloed, 1986.

Honings, W. & P. van Zonneveld, De gefnuikte arend. Het leven van Willem Bilderdijk (1756-1831). Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2013.

Kalff, G. (ed.), ‘Onuitgegeven brieven van Bilderdijk aan Feith’, in Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde 24, 1905.

Kollewijn, R.A., Bilderdijk. Zijn leven en zijn werken. 2 dln. Amsterdam 1891.

Lodewick, H.J.M.F., Literatuur. Geschiedenis en bloemlezing. Den Bosch: Malmberg, 1985.