Reading a Korean edition of the Diamond Sutra

On view in the National Museum of Ethnology a very special 1578 copy of the Diamond Sutra.

The National Museum of Ethnology currently (until 21 January 2019) has a small exhibition on Geumgangsan, the Diamond Mountains. This mountain range in the east of Korea is known as one of the most beautiful sights in Korea and holds a special place in Korean art and literature. Take for example the recent signing of the Panmunjeom statement: the room in which the leaders of North and South Korea signed the agreement had a large painting of the mountains as backdrop. The eponymous diamond refers to the vajra, originally the thunderbolt of Indra, in Buddhism it came to symbolize hardness and indestructibility.

The Special Collections of Leiden University Libraries were so kind to lend one the most important pieces of their Korean collections to be shown in the exhibition, namely a 1578 copy of the Diamond Sutra from the collection of Robert van Gulik (1910-1967), the well-known Leiden Sinologist. There are rather few examples of early Joseon bookprinting extant, so to have this edition in our museum is a rare treat. Unfortunately it is impossible to show every page in the exhibition, but I will point out some points of interest in this blog post.

The sutra was stored in a blue cloth case. On the title cartouche is written an abbreviated title and the land in which it was produced: 朝鮮般若會變相, illustrated gathering of wisdom from Chosŏn. This case is relatively new and probably made for the Japanese collector who owned this sutra before it came into the possession of van Gulik. From 1910 to 1945 the Japanese empire ruled Korea. During this era of colonial rule many Korean antiquities, ceramics, and rare books ended up in Japanese collections.

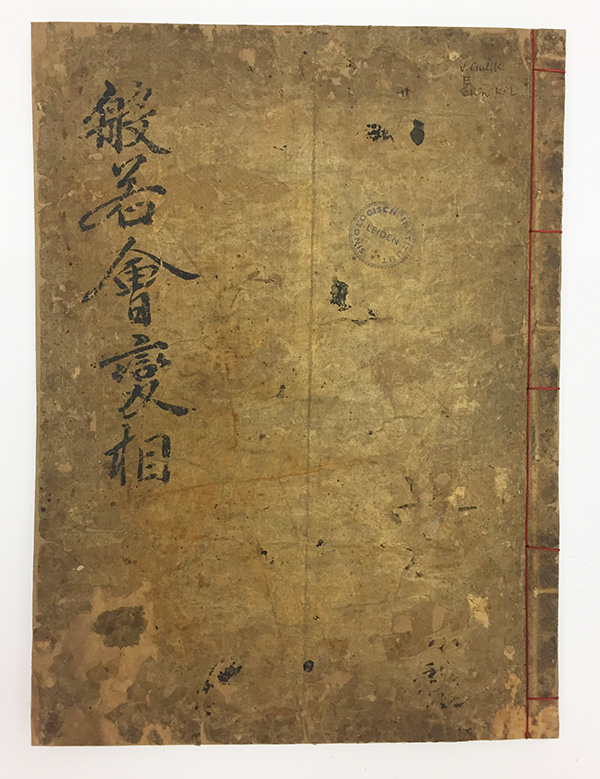

The sutra itself is a single volume, bound in a side-stitched binding with paper covers. Although during the preceding Goryeo period (918-1392) various bookbinding methods were used, during the Joseon period the side-stitched binding is the most common. On the right of the cover we see the red threads stitching the book together. Korean books of the Joseon period are usually bound in red thread with five stitches, unlike Chinese books which are most often bound in four.

The cover of the book is called the Chaekui冊衣, i.e. the book’s clothes. In this case the book is dressed in a cover made from several layers of paper, which were often recycled from discarded books or manuscripts. The top layer of such covers is usually dyed to a yellow colour and then finished with beeswax to create a sturdy and water resistant finish. Not every book dresses in the same clothes however, and valuable editions could sometimes receive a cover made from silk. Although the contents of the sutra are woodblock printed, the characters of the abbreviated title are handwritten with a brush in a semi-cursive script.

First page.

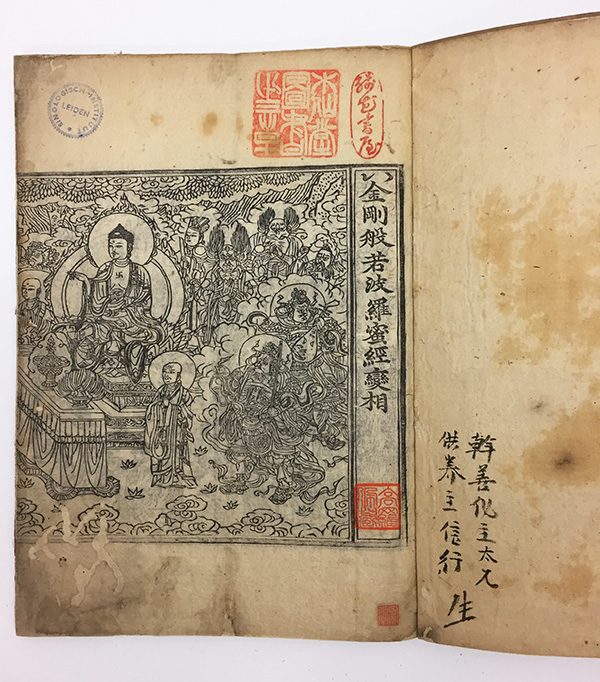

Opening the sutra, we find one of the most beautiful illustrations in the sutra: the frontispiece showing a heavenly assembly with the Buddha surrounded by bodhisattvas and heavenly kings. Here we also find the full title of the work金剛般若波羅蜜經變相, Illustrated version of the Diamond of Transcendent Wisdom sutra.

Various collection seals are found on the first page. For example, just below the title we find the seal高羅佩藏, the collection of Gao Luopei, i.e. Robert van Gulik. On the right page we find an inscription telling that this printed edition was the result of gifts from various benefactors.

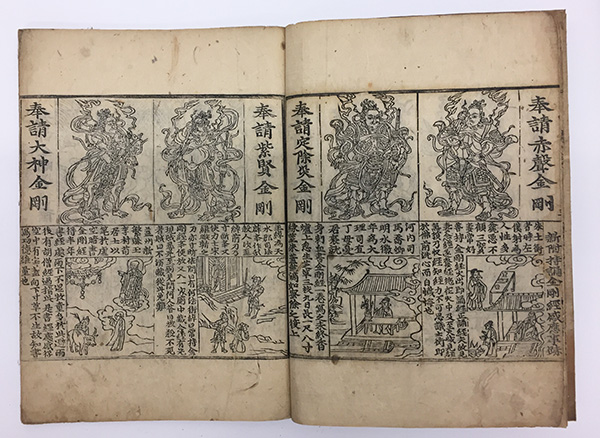

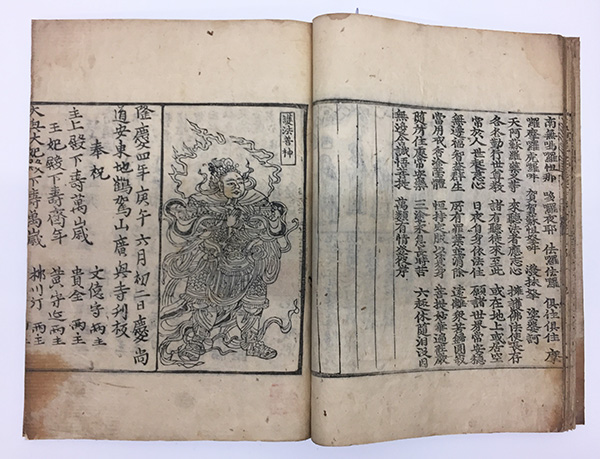

Geumgangyeoksa.

As you might have gleamed from the title, this is no ordinary edition. The use of woodblock printing allows for the inclusion of various illustrations in order to explain the text. Here for example, we see the Geumgangyeoksa, muscled guardian figures.

Buddhism and printing have a long and interwoven history in Korea. One of the oldest extant woodblock printed texts in the world is a Dharani Sutra dated 751, found in Bulguksa temple in Gyeongju in 1966. The second Koryo tripitaka made in 1236 is the oldest extant set of printing blocks of the Buddhist canon. The 81.258 woodblocks are stored today at the Haeinsa temple.

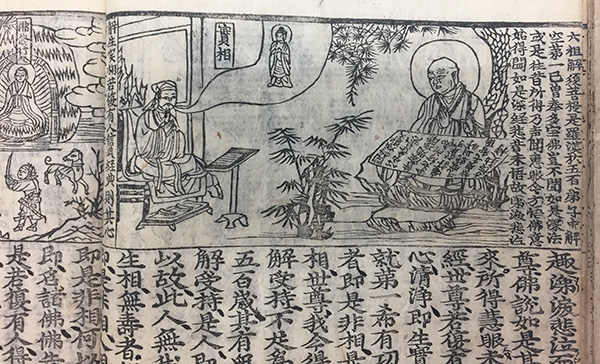

Silsang: the ultimate essence of things.

The Diamond Sutra is one of the basic texts in Korean Buddhism and is chanted on a daily basis still today. The text records a conversation between the Buddha and Subhūti, one of his pupils, in which the Buddha calls into question the validity of conceptual labels. The eponymous Diamond then serves as a metaphor for the Buddhist truth cutting through illusion.

After the end of the main text there is one final illustration: the deva who protects the dharma. Now starts what may be called the colophon of the Sutra, beginning with the place and time of production.

隆慶四年庚午六月初二日慶尚道安東地鶴駕山廣興寺刋板

“On the second day of the sixth month in the fourth year of the Longqing reign (1570) the Hakgasan Gwangheungsa temple in the territory of Andong in Gyeongsangdo province cutted these blocks.”

Gwangheungsa temple by Robert at Picasa - 2006-08-12-Andong, CC BY 3.0

The temple of Gwangheungsa was founded during the reign of king Munmu of Silla (661-681) by the famous monk Uisang. It still exists today but the surviving structures are all from the Joseon period.

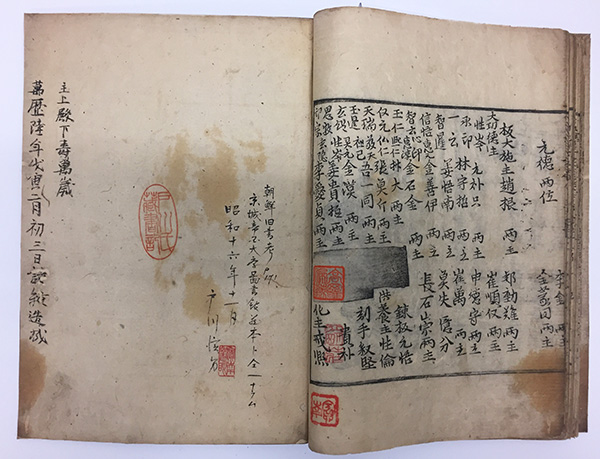

Colophon.

The colophon is then about to continue with the names of the various donors. First things first however. Before the donors are named proper respect needs to be paid to the royal family. 主上殿下壽萬歲 May his majesty the King live for ten thousand years!王妃殿下壽齊年May her majesty the princess consort live for the same amount of years! After these wishes to the royal family starts a long list with names of benefactors and monks who worked on the production of the printing blocks.

Today the Joseon dynasty is often seen as a strict Confucian society in which Buddhism was suppressed. There is some truth to this. The hereditary meritocrats of the Confucian elite monopolized state positions and set much of the political agenda. Buddhism no longer enjoyed the exalted position it had during the Goryeo periode, however Buddhism was still of relevance to the daily lives of people. Moreover, many female members of the royal family were actually ardent Buddhists and several Kings were so as well (though usually to the dismay of their ministers).

Last page.

On the end page of the sutra we find two inscriptions. On the right a Japanese owner, a certain mr. Togawa, notes that this edition is described in the book 朝鮮舊書考(study of old Korean books). This inscription is dated Showa 16 (1940). Two of his seals are found on this page.

The inscription on the left is from the time of printing. For good measure, the writer wishes the King to live for ten thousand years. It further tells us “finished on the third day of the second month in the sixth year of the Wanli reign.” Indicating that this particular impression was made in the year 1578. In the next few decades Korea would suffer several invasions, during which many printed works were lost. There are however still a few copies left of this sutra, which can be found in the national library of Korea, the Kyujanggak library of Seoul National University, the collections of the Beomeosa temple, and, of course, Leiden University Libraries.

Karwin Chi-on Cheung is Curatorial Assistant East Asia at the National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, The Netherlands