Rumphius and his Ambonese Herbal, a series of unfortunate events

Whilst scientists have achieved undeniable successes over the centuries, many of them endured more than their fair share of disappointments, failures and disasters. Who deserves the title of most unfortunate scientist is still up for debate.

A good candidate would be, for example, the French astronomer Guillaume Le Gentil, who missed the Venus Transit twice. Or think of the British naturalist Alfred Wallace, who saw four years’ worth of collecting in the Amazon go up in flames from a lifeboat. Other contenders are the British palaeontologist Mary Anning, who watched in dismay as gentlemen invariably took credit for her discoveries, or the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, who lost his head to the guillotine. Not to mention the continued disbelief endured by naturalists like Gregor Mendel, Ludwig Boltzmann and Ignaz Semmelweis. This list of unfortunate scientists also includes the name Georg Everhard Rumphius. The life of this rather unknown Hessian naturalist reads like a tragedy.

From an early age, disaster seemed to follow Rumphius around. As soon as he left his parental home in Wölfersheim, out of a self-proclaimed love of science, he was recruited to serve as cannon fodder in the Dutch-Portuguese War in Brazil. On his voyage to Brazil, the yacht De Swarte Raaf was damaged off the coast of Spain, and the young Rumphius was taken as a prisoner of war by the Portuguese. After several years of compulsory service in a foreign legion of the Portuguese army, he was discharged. Returning to Holland, he registered with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to sail to the East. On the second day of Christmas 1652, Rumphius embarked on his journey to Batavia, and later onwards to his final destination, the island of Ambon, where he would stay until his death in 1702. Despite the fact that upon arrival in Batavia he was enlisted to fight in the Great Ambonese War, Rumphius' first years on the Moluccan island passed without any large mishaps. He worked his way up the army ranks and eventually managed to get a civilian position as a junior merchant and later as a merchant. This position allowed him to pursue his passion and study the flora and fauna of the Moluccas. But in 1670 fate strikes again. Due to glaucoma, Rumphius became incurably blind and he was forced to lay down his work. Fortunately, with the assistance of his wife Susanna and son Paul August and help from the East India Company he was able to continue his studies. Four years later, he was a blind witness to the worst natural disaster in the Moluccas of the seventeenth century, a terrible earthquake that cost the lives of more than 2,300 people, including his wife and two of his children. Nevertheless, Rumphius continued to work with Job-like patience on the completion of one of the most extensive botanical works of the seventeenth century: The Ambonese Herbal. This book also had its fair share of bad luck.

Books, too, are known to have their ‘dark hours’. Some are burnt at the stake, condemned to the Vatican's blacklist or simply thrown in the shredder. Other books suffer from censorship, fatwas and bad translations. On several occasions, the survival of The Ambonese Herbal was hanging by a thread. For example, the first six books lie at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. During its return voyage to the Netherlands, the ship Waterlandt was attacked by the French and sunk in the Bay of Biscay in 1692. The last six books almost perished in a fire, when Rumphius’ house burned to the ground in 1687. Fortunately, the manuscripts could be saved, but a large portion of the illustrations was consumed by the flames.

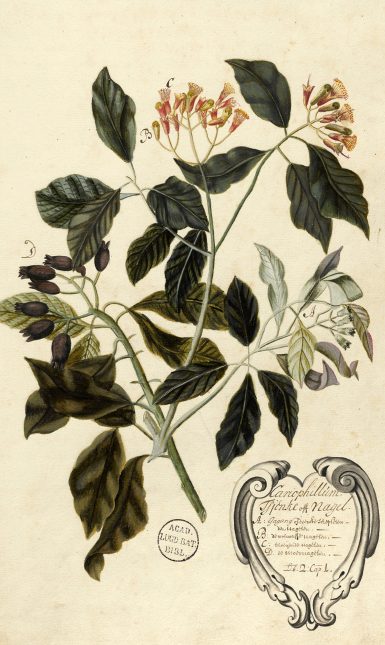

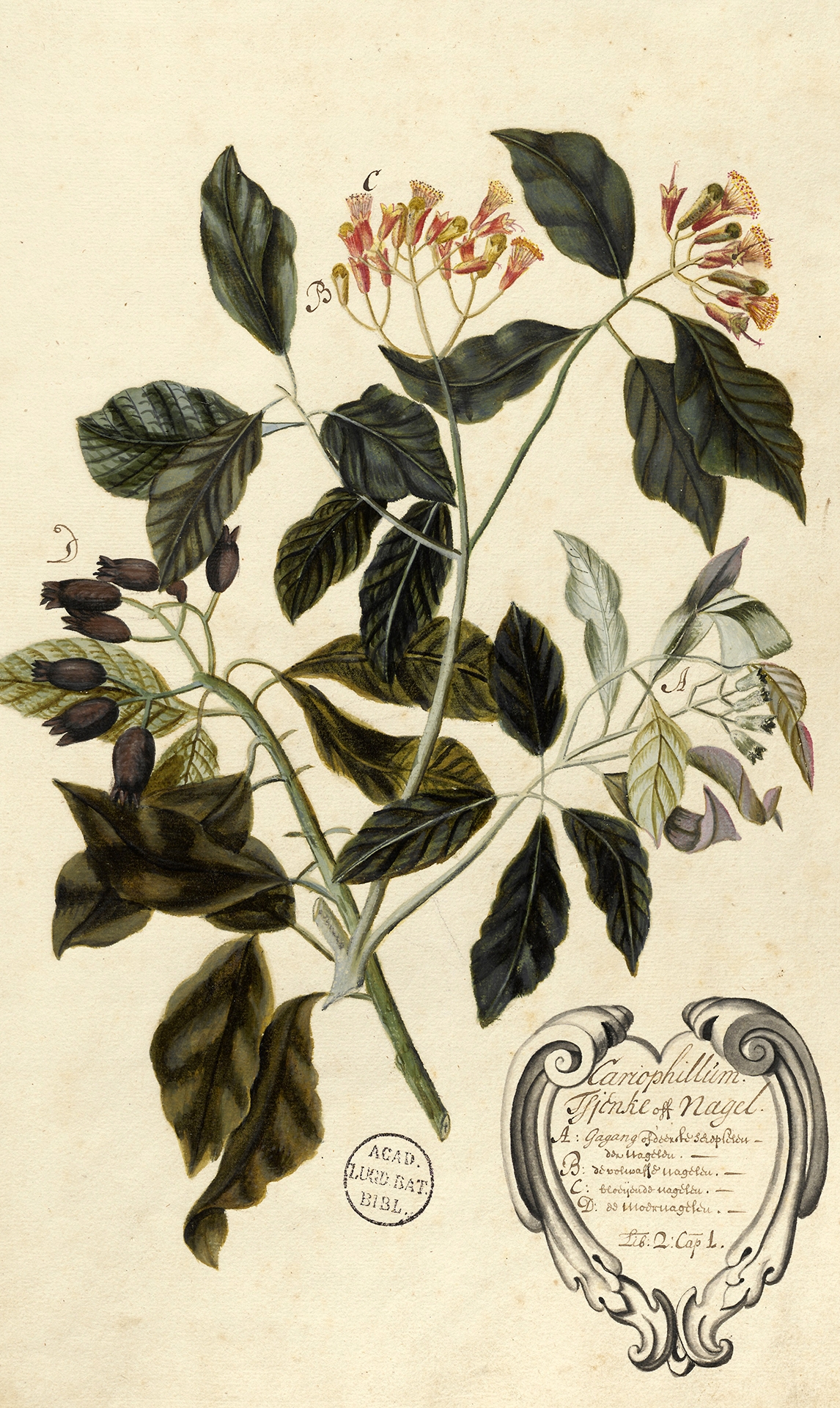

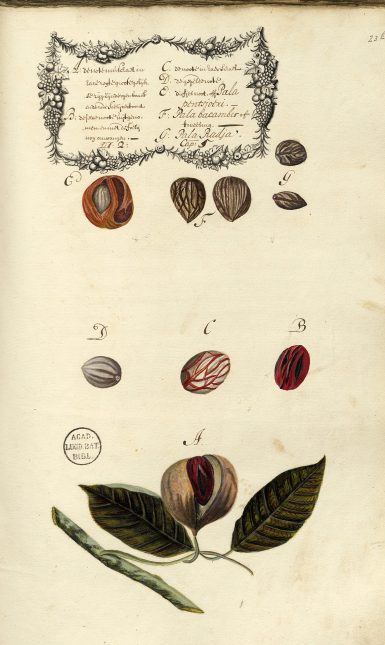

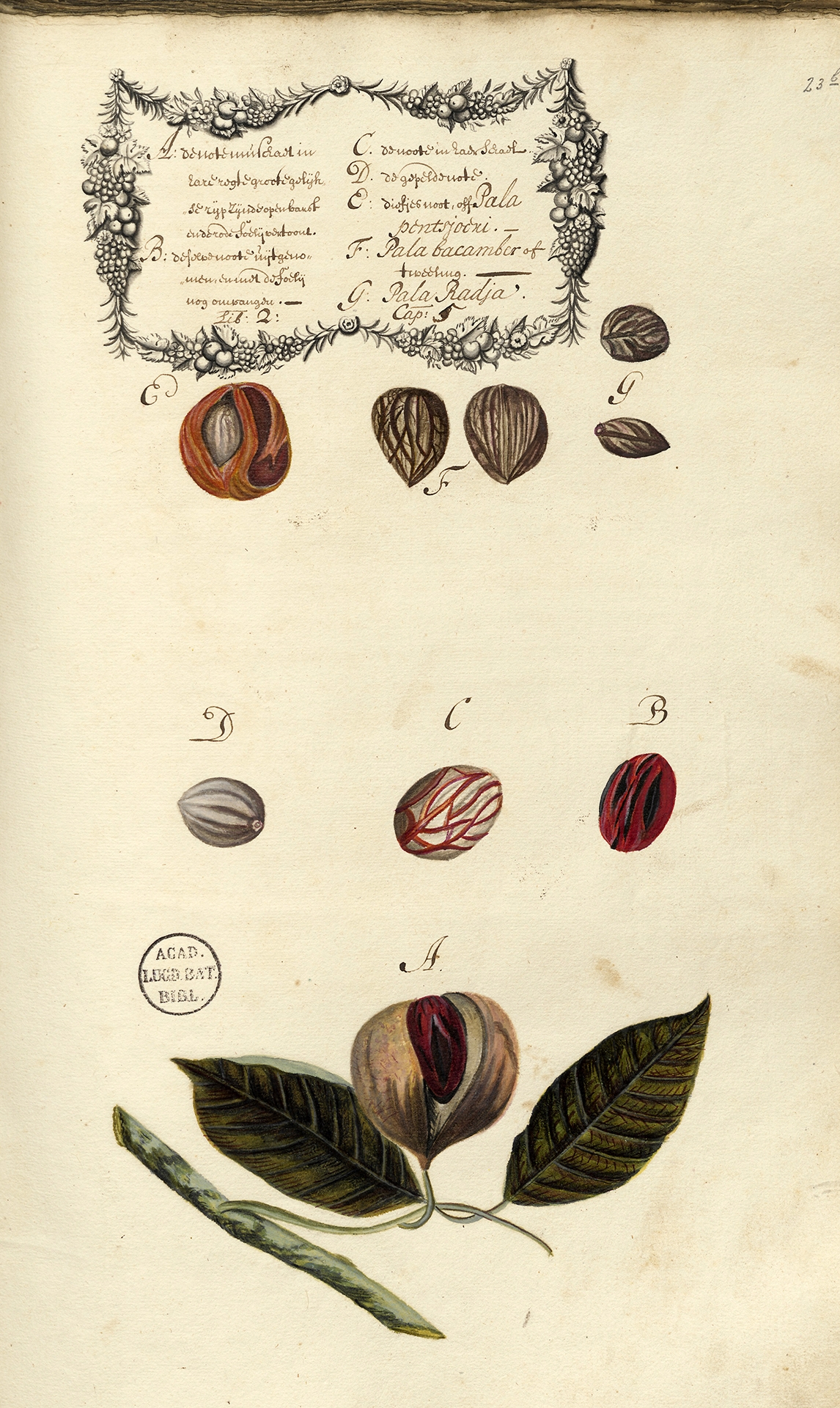

Luckily The Ambonese Herbal persevered this trial by water and fire. We owe the survival of the first half of Rumphius’ masterpiece to the interest of a single affluent reader. Two years before the maritime disaster took place, VOC Governor-General Johannes Camphuys received the first six parts. He was so impressed by Rumphius’ as yet unfinished masterpiece that he decided to resign from office to study the herbal at leisure. Fortunately, he ordered a copy of the manuscript to be made before having it shipped to the Dutch Republic. After the disaster in 1692, the first six parts eventually arrived in 1696 (by that time supplemented with three new parts), followed in the next years by the last three parts and an accompanying index. However, even upon arrival, the manuscript did not find its way to a publisher. During the first years the Heeren XVII, the executive council of the VOC consisting of seventeen members, locked the manuscript in their vaults because it contained sensitive information that could hinder their monopoly in the spice trade. Rumphius wrote extensive descriptions of, for example, the clove-tree and nutmeg tree, plants that were an apple of contention between the European colonial powers at the time. After a few years, the embargo was lifted, but now there were insufficient funds to print the herbal. Eventually, it was the Dutch botanist, Johannes Burman, who prepared the manuscript for publication. He translated the Dutch text into Latin, thus providing a bilingual edition. In the end, a consortium of five publishers was needed to print the book. The first part rolled of the press in 1741; 39 years after the death of its author.

Despite the turbulent past of Rumphius´ Ambonese Herbal, the two oldest handwritten manuscripts are now safely stored in the Special Collections of the Leiden University Libraries. You only need a LU-card to browse through this remarkable botanical masterpiece in person, which is highly recommended. Leafing through the herbal you will notice how much of the Ambonese (and Moluccan) culture is intertwined with the flora of this region, and the plants described offer a unique window into seventeenth-century island life. Not only is the work of great importance to the tropical botany of Southeast Asia, it still contains numerous undiscovered treasures for people with an interest in ethnography, linguistics, history and medicine.

On the author: Norbert Peeters is a PhD student at the Institute for Philosophy, who recently published his book: Rumphius’ Kruidboek. Verhalen uit de Ambonese flora.