Short Notes and Scribbles in Malay Manuscripts

Seemingly insignificant scribbles such as notes or writing exercises in the margins or on the flyleaves of manuscripts, may reveal information that is not found elsewhere.

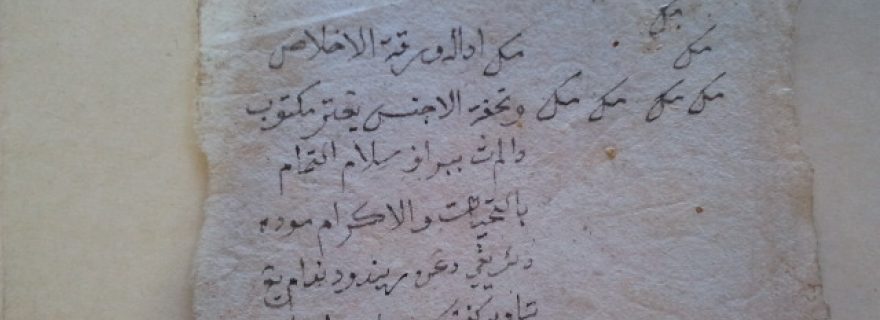

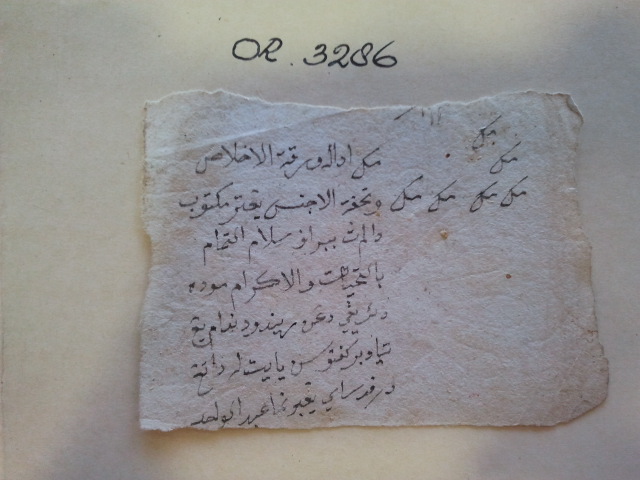

Short letter between the pages

In this note in Malay on a snippet of scrap paper a certain haji Abdul Wahid conveys his greetings and ‘everlasting’ warm regards. The text does not mention the name of the addressee. The unpretentious short letter was found concealed between the pages of a Malay manuscript that was acquired by the Bible translator and linguist Herman Neubronner van der Tuuk (1824–1894) on Sumatra’s northwest coast.

Van Der Tuuk's frustrated search

Van der Tuuk was posted in the small trade port community of Barus between 1851 and 1857 as a Bible translator in the service of the Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap (Dutch Bible Society). Although his main task was to produce a translation of the Bible in one of the Batak languages, he also tried his pen at translating into Malay. To further his study of written Malay he collected Malay manuscripts. But for Van der Tuuk working conditions in Barus – an outpost only re-colonised a decade earlier – turned out to be far from ideal. When he found out that the Muslim Malays were reluctant to sell their coveted manuscripts to an impure unbeliever, he began a fruitless search for able copyists. His long letters to the Board of the Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap give evidence of his endless frustration about the fact that Barus had no commercial copyists.

Working together with a copyist

It is in this particular light that the scribbled note gains significance. Together with the name of Abdul Wahid, found in the colophon of two of Van der Tuuk’s Malay manuscripts, and a draft letter that can be attributed to this same person, the note indicates that Van der Tuuk did find at least one copyist. From the draft letter it can be inferred that this Abdul Wahid worked in the neighbouring port settlement of Sorkam as a clerk for the local élite. It was probably through Van der Tuuk’s contacts with the raja of Sorkam that he finally succeeded in finding someone who could help him with his copying. It is not difficult to image the note being placed by the scribe between the pages of a copy that was to be delivered to Van der Tuuk’s house in Barus (Or. 3286). Notwithstanding its small size, the letter is important: it is the only source that provides proof of the existence of a working relationship between Van der Tuuk and the copyist haji Abdul Wahid.

Missing piece of the puzzle

Since almost all our knowledge of nineteenth-century Malay writing is based on manuscripts, it is necessary to gather information about the circumstances under which Malay manuscript were collected. With the scarcity and fragmentary nature of other sources, scribbles and drafts sometimes provide the missing piece of the puzzle.

Blog post by Marije Plomp, Subject librarian at Leiden University Libraries