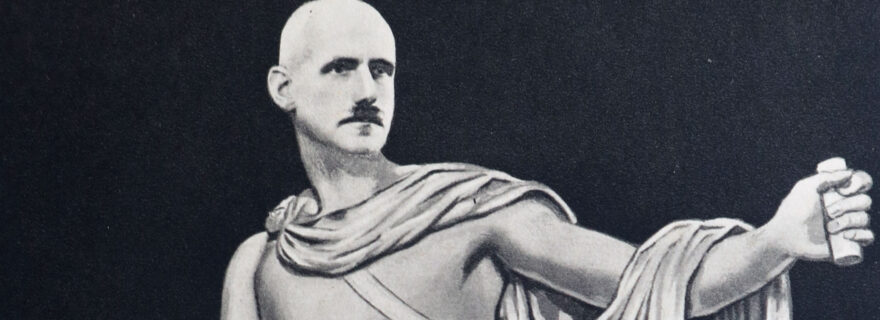

The Augustan rector

There must have been some chuckling when guests at the rector's dinner on the 8th of February 1940 opened their menus. On the inside the rector magnificus was depicted as a small putto next to Augustus of Prima Porta. Was it meant as a witty conversation starter, or was there a deeper meaning?

The occasion of the dinner was the 365th Dies Natalis of Leiden University. The celebrations were understandably subdued. Although the Netherlands was still neutral, the continent was in the grip of war. Public celebrations in the city and most student festivities were therefore canceled. But rector magnificus Frederik Muller Jzn. (1883-1944) delivered the traditional Dies speech in the large auditorium of the Academy Building and in the evening the professors concluded the Dies with the traditional dinner at Maison Bruyns on the Rapenburg.

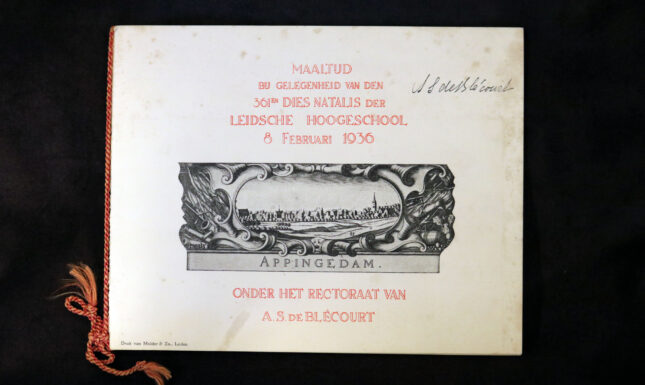

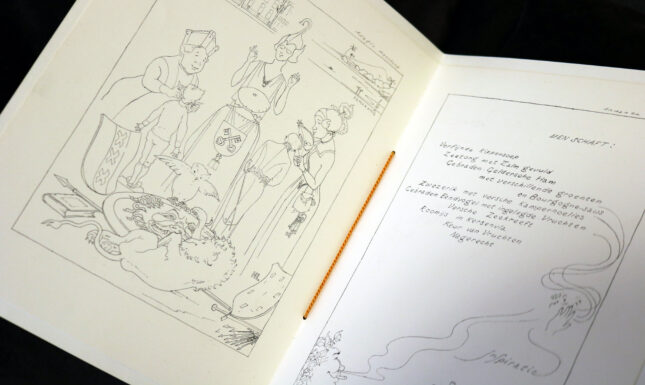

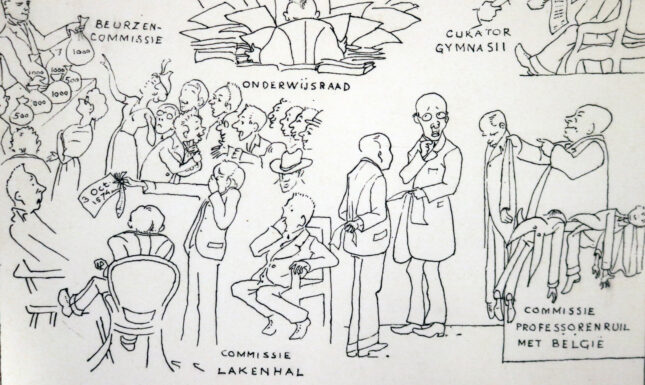

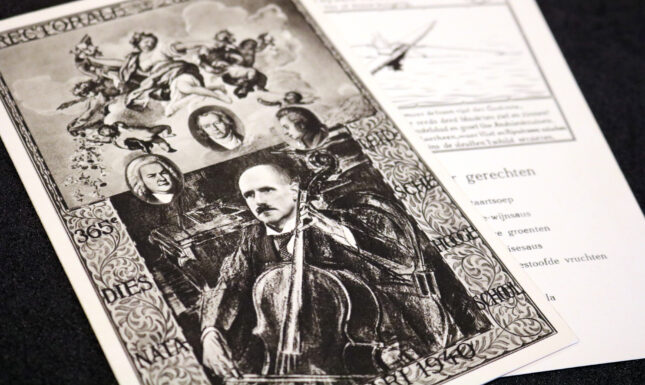

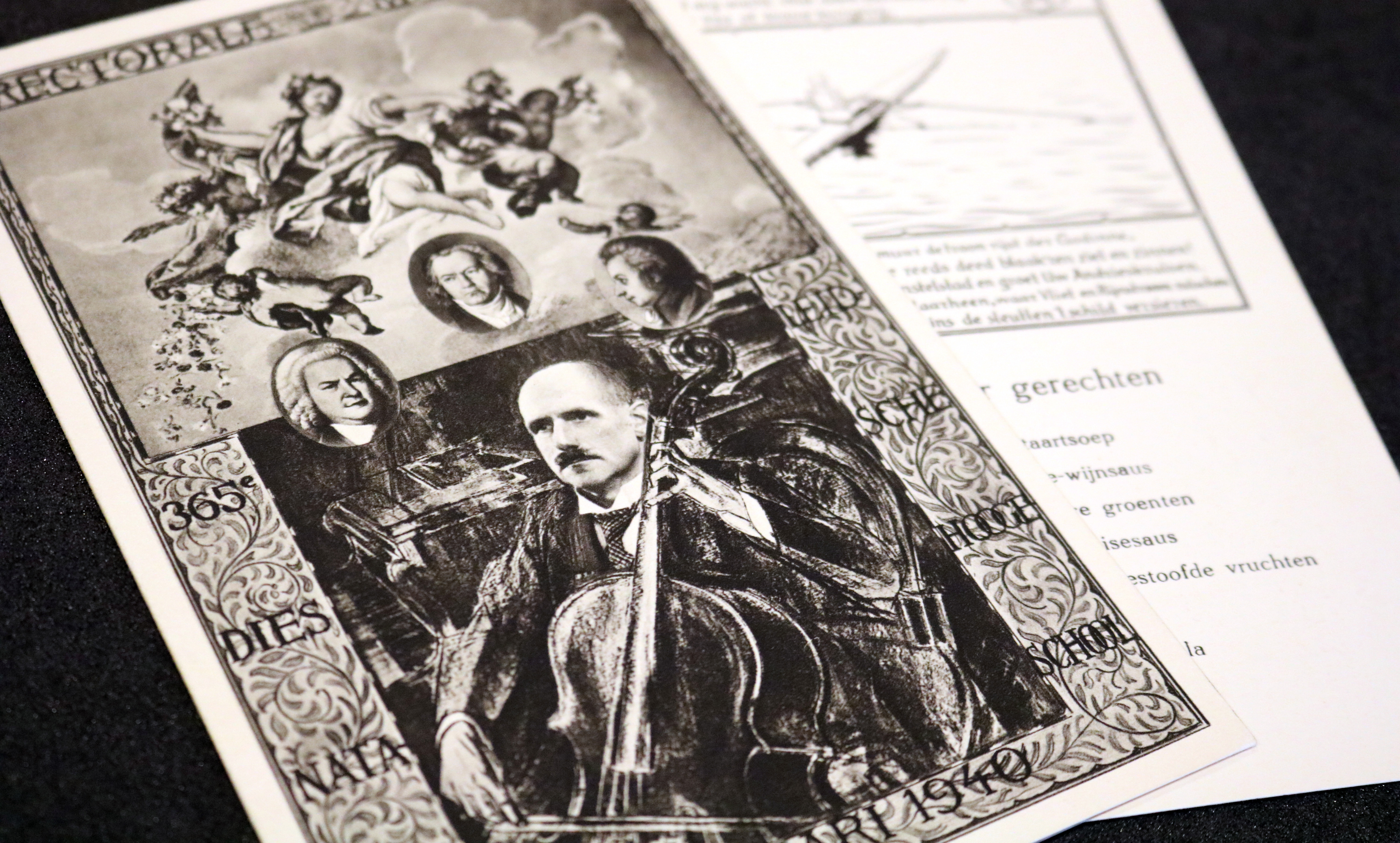

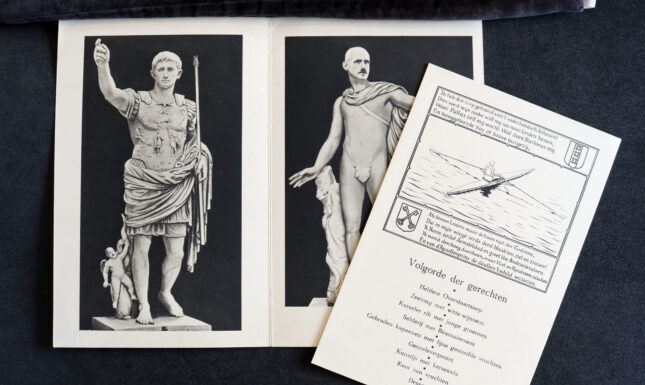

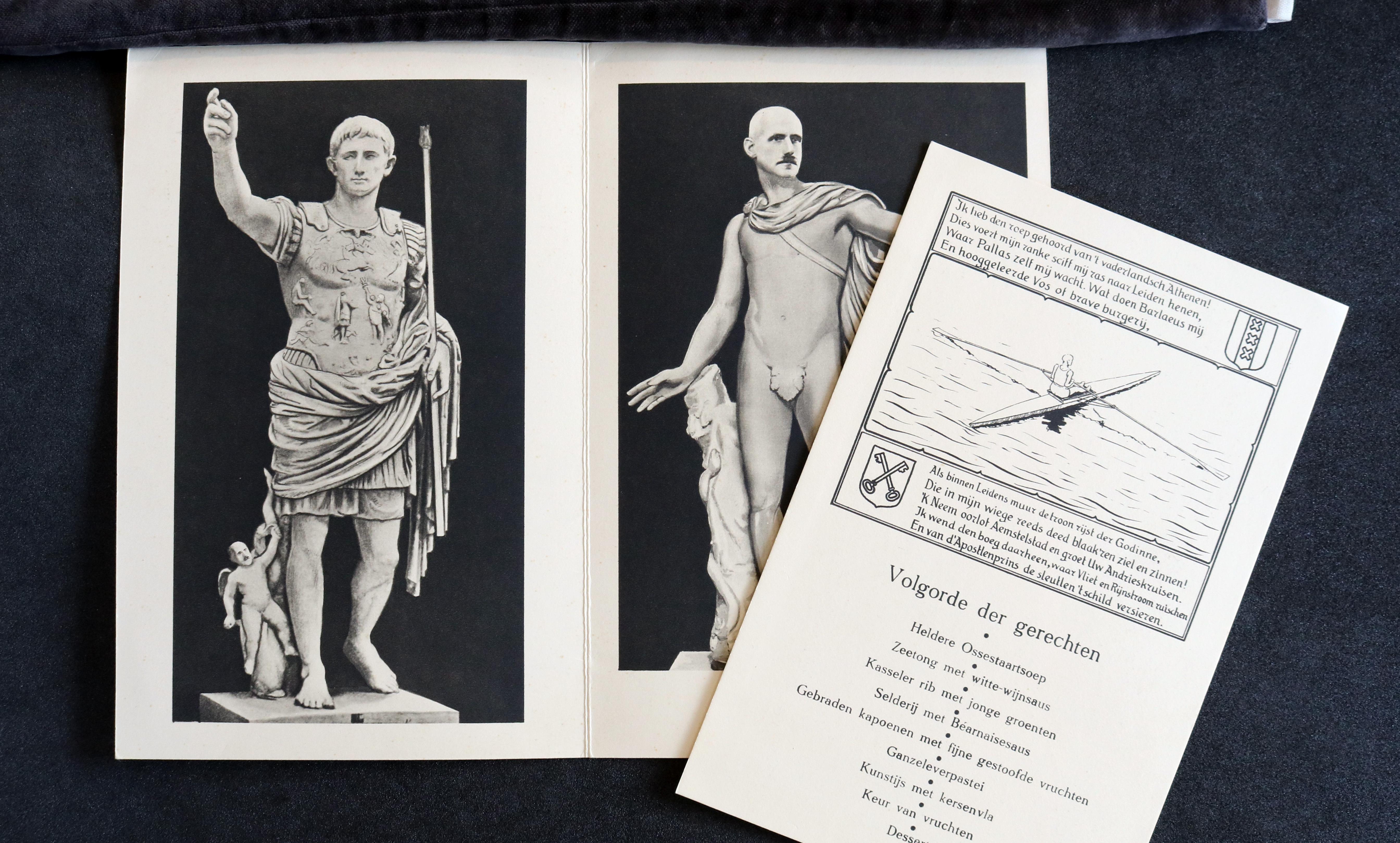

Images 1-4: Menus of the dinners in 1937 (AHM-1939-77/1), 1936 (AHM-1995-138/7) and 1938 (AHM-1938-14).

It had been customary for a number of years that a playful menu was designed for this occasion. The main topic of these menus was the rector magnificus. Because the rectorship rotated annually until 1972, there was a new rector every year who could serve as inspiration. In many cases, the menus appear to have been made by befriended colleagues. For instance, Johan Huizinga (1872-1945, rector in 1932-1933) and Ton Barge (1884-1952, rector in 1936-1937) were both member of the walking club ‘De Beentjes’ (‘The Legs’) and designed each other’s menus.

It is not known who made the menu for Muller, but whoever made the menu, it seems that quite some time was invested in it. Images of works of art have been manipulated and supplied with Muller’s portrait. On the front, we see Muller playing the cello (a customization of a print from 1918 by Jan Toorop of Adrian-Paul Mignot), accompanied by Bach, Beethoven and Mozart. Above the three composers, a goddess is depicted: a copy of a fresco of the triumphant Flora in the Villa Falconieri in Rome. On the back, we find the emblem used by book seller and print collector Frederik Muller (1817-1881), grandfather of the rector. As mentioned, the inside of the menu was decorated with adaptations of the Augustus of Prima Porta and the Apollo of Belvedere.

Both statues refer to Mullers field of expertise in general - he was professor of Latin - and more directly to the subject of the speech he had given earlier that day. Muller had spoken on the revival of the Roman might under the rule of the emperor Augustus and the relation between Augustus and the god Apollo.

Although the direct reference of both images is clear, the image of Muller pulling on Augustus' skirt in particular is also a little bit uncomfortable. Augustus was certainly not an apolitical subject in the late 1930s: in fascist Italy and, to a lesser extent, Germany, the first Roman emperor was viewed with admiration and had been the subject of many recent studies.

Muller himself was also far from unproblematic. In the words of his successor Jan Hendrik Waszink (1908-1990), Muller had “a preference for all things German,” both in the scientific field and within the broader cultural sphere. The rise of Nazism had not exactly cooled this love. Those who had expected words of warning from rector Muller were disappointed: in various speeches in 1939 and 1940, he expressed his belief that the war would bring a new, beneficial era. When he handed over the rectorship to Alexander Willem Byvanck (1884-1970) in September 1940 – two months before the speeches by Cleveringa, Barge, and Van Holk defending their Jewish colleagues – Muller, in contrast, urged his audience to show obedience and discipline.

Despite his pro-German sentiments and his somewhat difficult character in general, Muller was not necessarily an outsider among the Leiden professors. For instance, when he died in 1944, there was some discomfort about how Muller's celebrated achievements as a scientist could be reconciled with his ‘missteps’ (as they put it mildly) during the Second World War. It is perhaps this same awkwardness that we see reflected in a toned-down message on the menu: a slightly mocking (and sadly unheeded) warning that Muller should not allow himself to be carried away by Augustus and his German and Italian fans.

With thanks to Bram van der Velden.