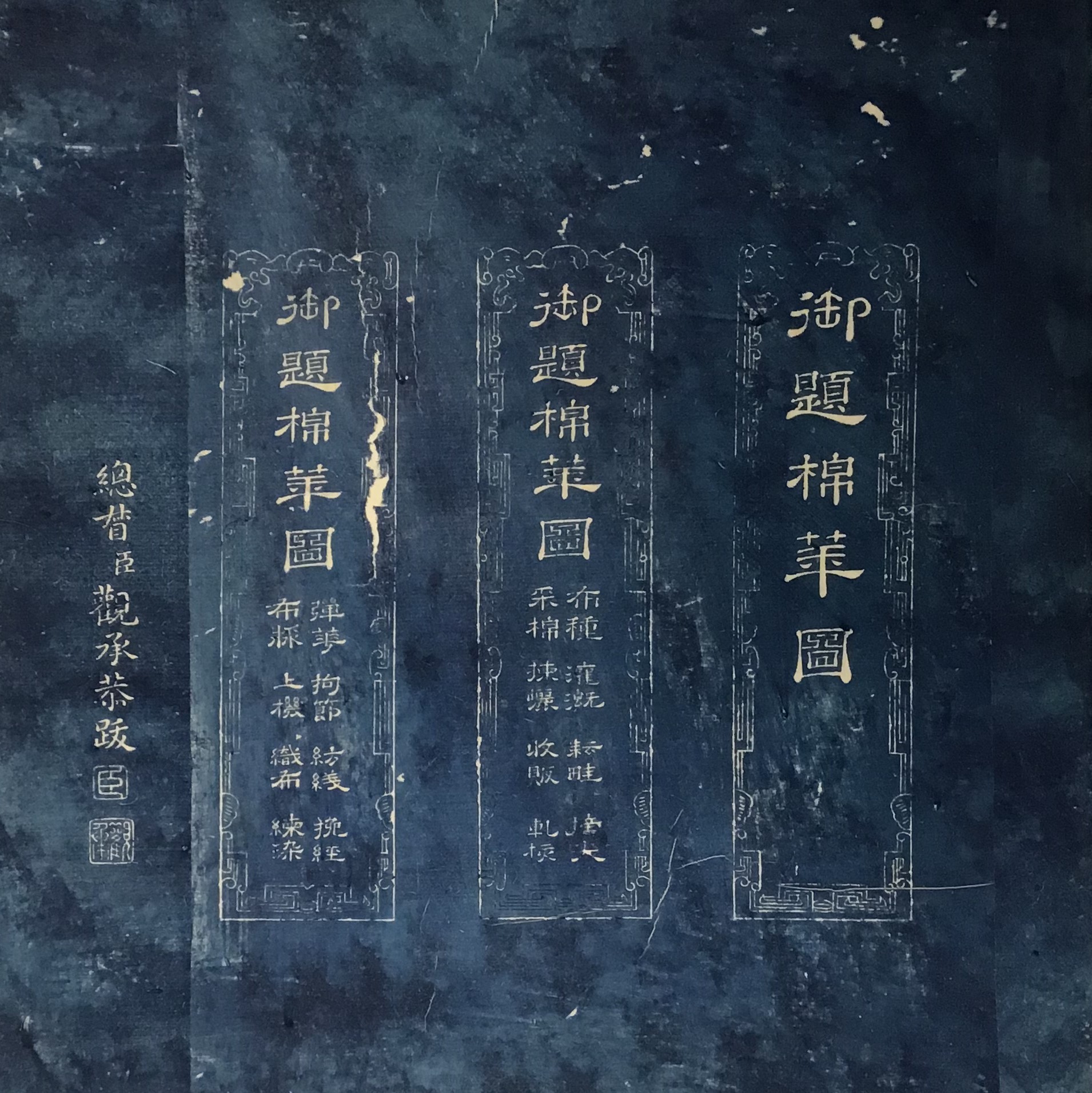

The Imperially Inscribed Illustrations of Cotton

Cotton production and Chinese imperial poems in blue ink: a new set of stone rubbings in the Leiden collection

China is the largest cotton producer in the world today. However, this was not the case a millennium ago. Cotton is not native to China. Only after the twelfth century was cotton extensively cultivated in Fujian, Guangdong, and the lower Yangtze River Region. In the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), cotton was widely grown in the north to provide raw material for clothing, and, most importantly, generate substantial local revenue.

Figures 1: The cover page of The Imperially Inscribed Illustrations of Cotton.

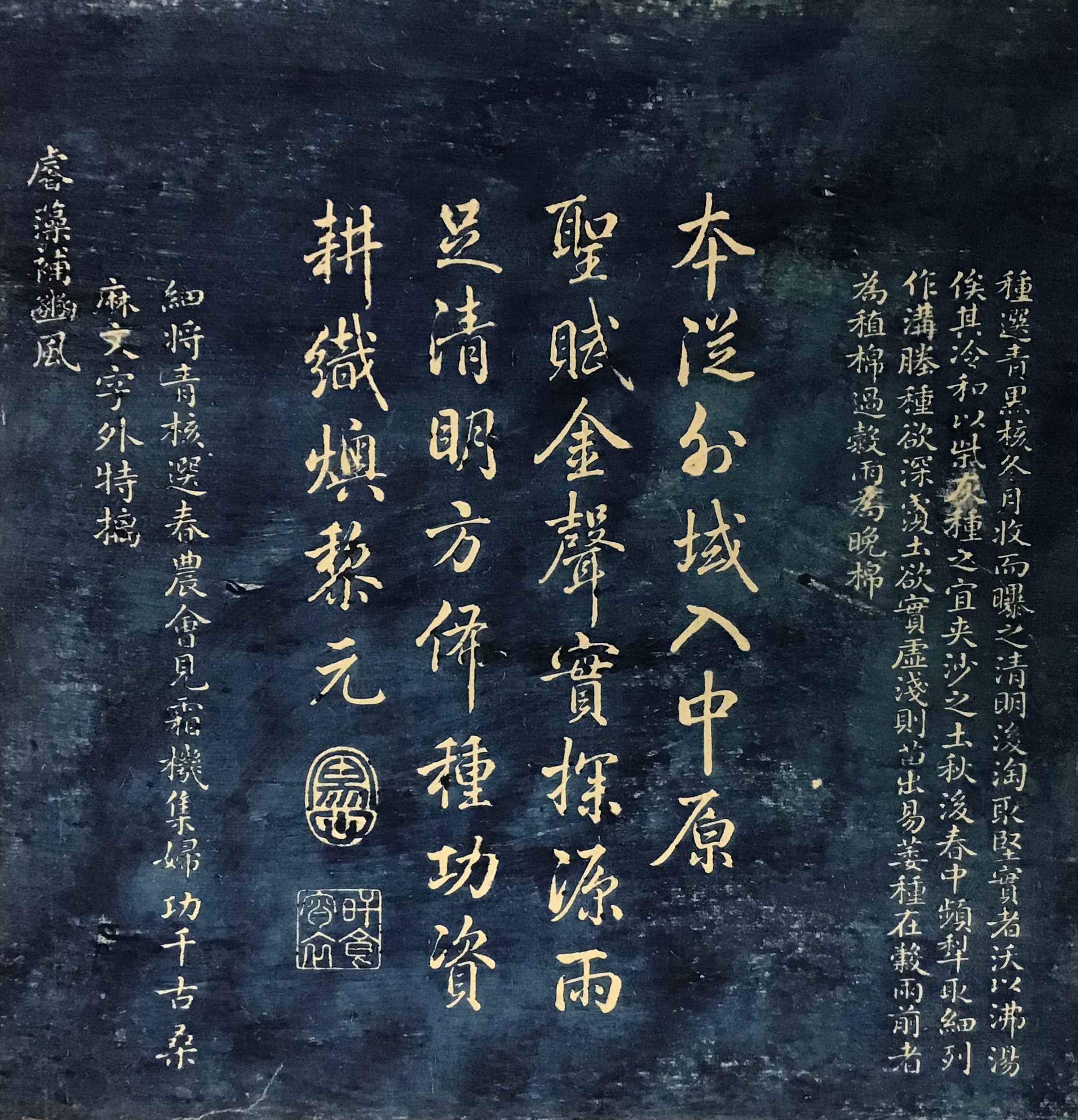

In 1756, when Fang Guancheng 方觀承 (1698-1768), the governor-general of the Zhili Metropolitan region, submitted The Illustrations of Cotton (Mianhua tu 棉花圖) to Emperor Qianlong 乾隆 (r. 1735-1796), the role of cotton in agricultural economy had been fully acknowledged by the state. Fang’s illustrations comprise of sixteen scenes, each depicting a step in the process of cotton cultivation and textile production (Figure 1). Qianlong promptly composed sixteen poems, one for each of the sixteen scenes. Fang subsequently ordered the carving of Qianlong’s poems, alongside his own encomia for Qianlong’s pieces, instructions for cotton production, and accompanying illustrations. Fang proudly acclaimed that the poems by the emperor was an official endorsement, which would make up for the absence of cotton in ancient Chinese classics (Figures 2-3).

The steles were first preserved in the government compound of Zhili region, then the Native-place Association of Liang-Jiang (Liangjiang huiguan 兩江會館), and now in the Hebei Provincial museum. The rubbings, entitled The Imperially Inscribed Illustrations of Cotton (Yuti mianhuatu 御題棉花圖), which was recently acquired by the Leiden University Libraries, was made after this set of steles.

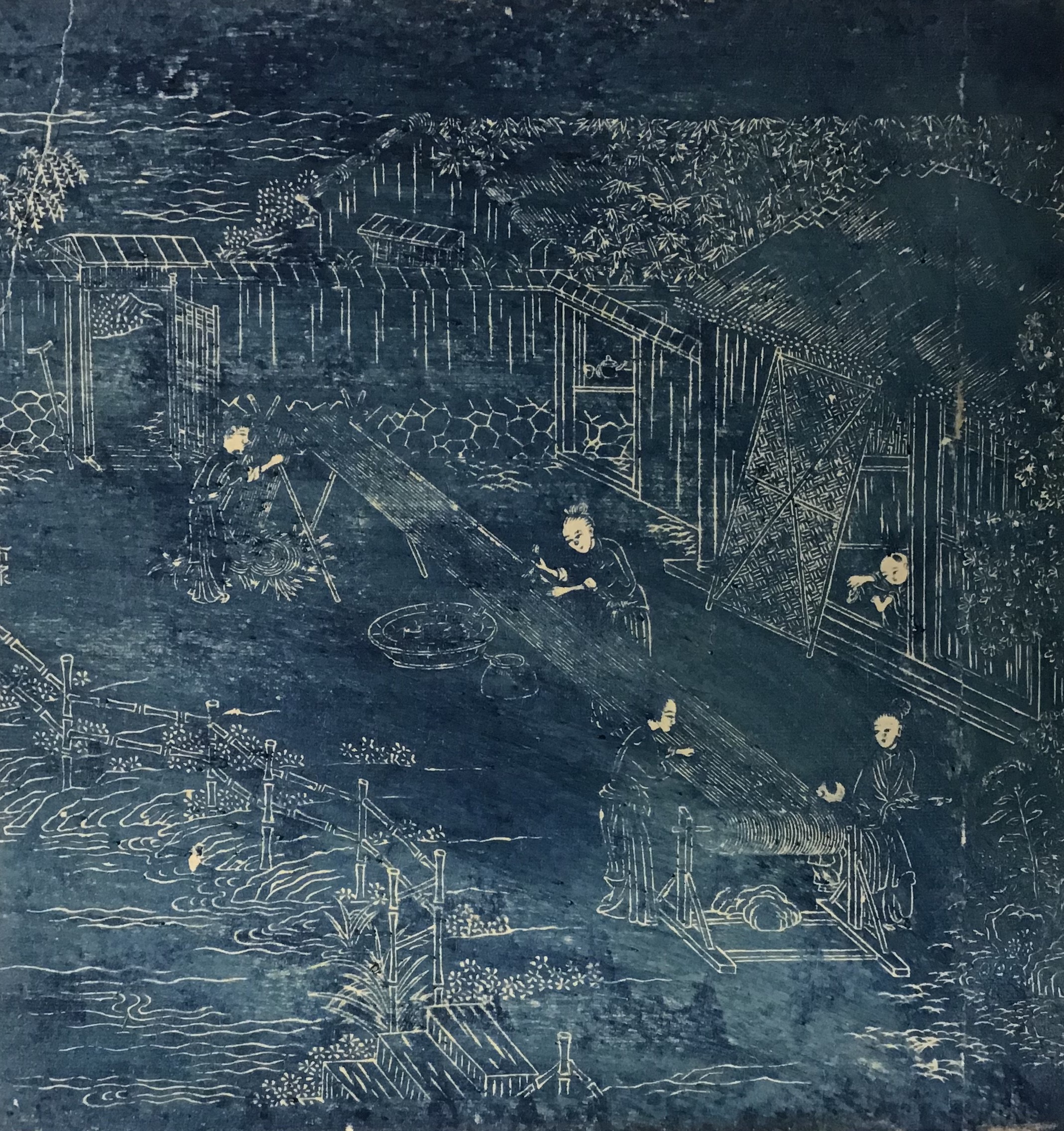

Figures 2-3: “Sowing Seeds” (Buzhong 佈種), in The Imperially Inscribed Illustrations of Cotton. The second couplet of Fang’s poem reads, “Although [cotton] has not been [mentioned] in the writings about mulberry (a metonymy for silk) and hemp, I especially present the words from the emperor to supplement the “Air of Bin’” 千古桑麻文字外,特摛睿藻補豳風. “The Air of Bin” is a section from The Book of Odes, one of the Five Confucian Classics, and is traditionally associated with the life of peasants.

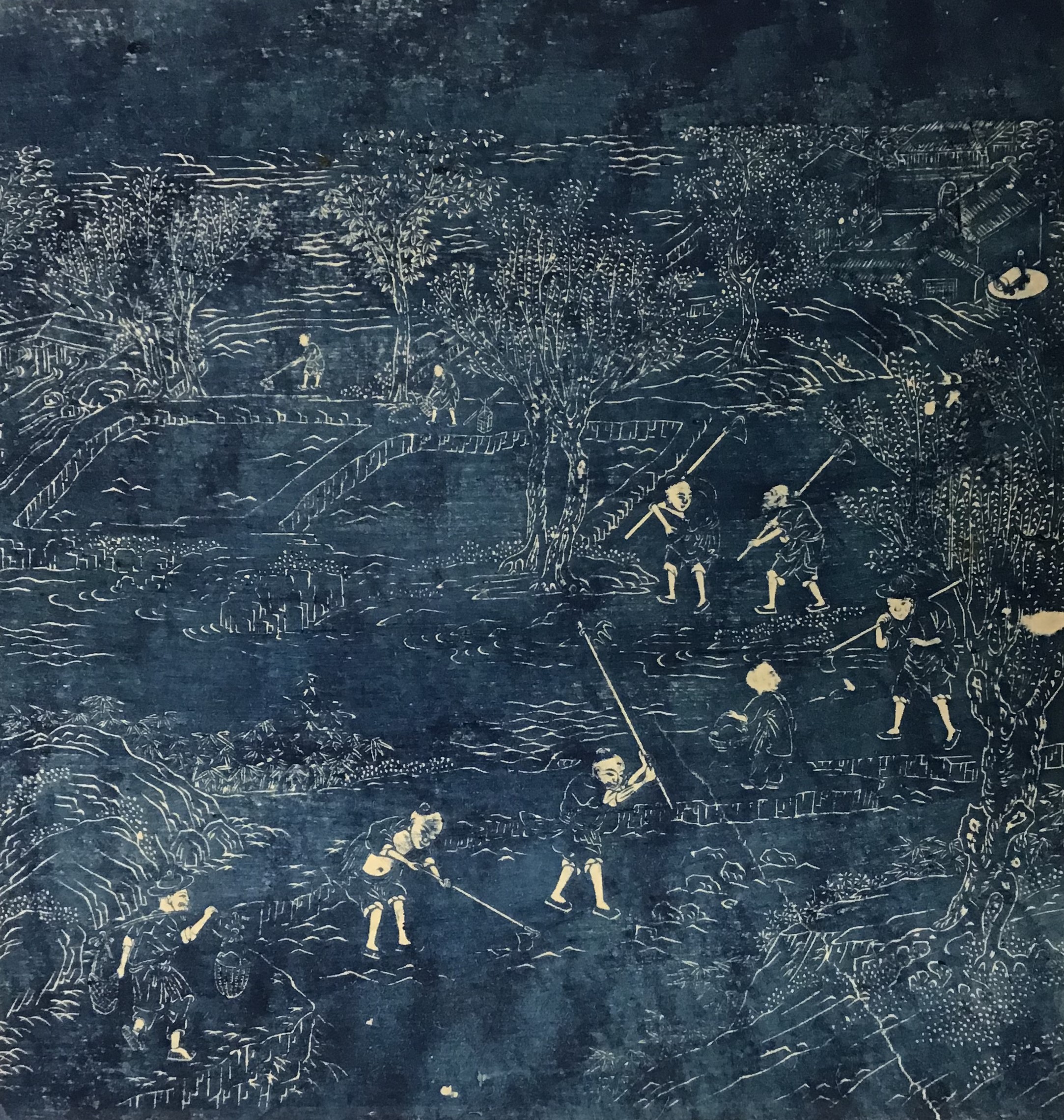

Fang’s instructions and illustrations show that he gained his knowledge about cotton from a broad range of texts and practices. However, unlike the widely-distributed Ming texts such as The Collection of Illustrations for the Convenience of the People (Bianmin tuzuan 便民圖纂) and Complete Treatise on Agricultural Activities (Nongzheng quanshu 農政全書), which tend to focus on early steps in cultivation including selecting seeds and sowing, The Imperially Inscribed Illustrations of Cotton presents a complete process of textile production from sowing seeds to irrigation, harvesting, trading, weaving, and dying. In his text, Fang localized the knowledge in each step by adapting it to the climate in Zhili.

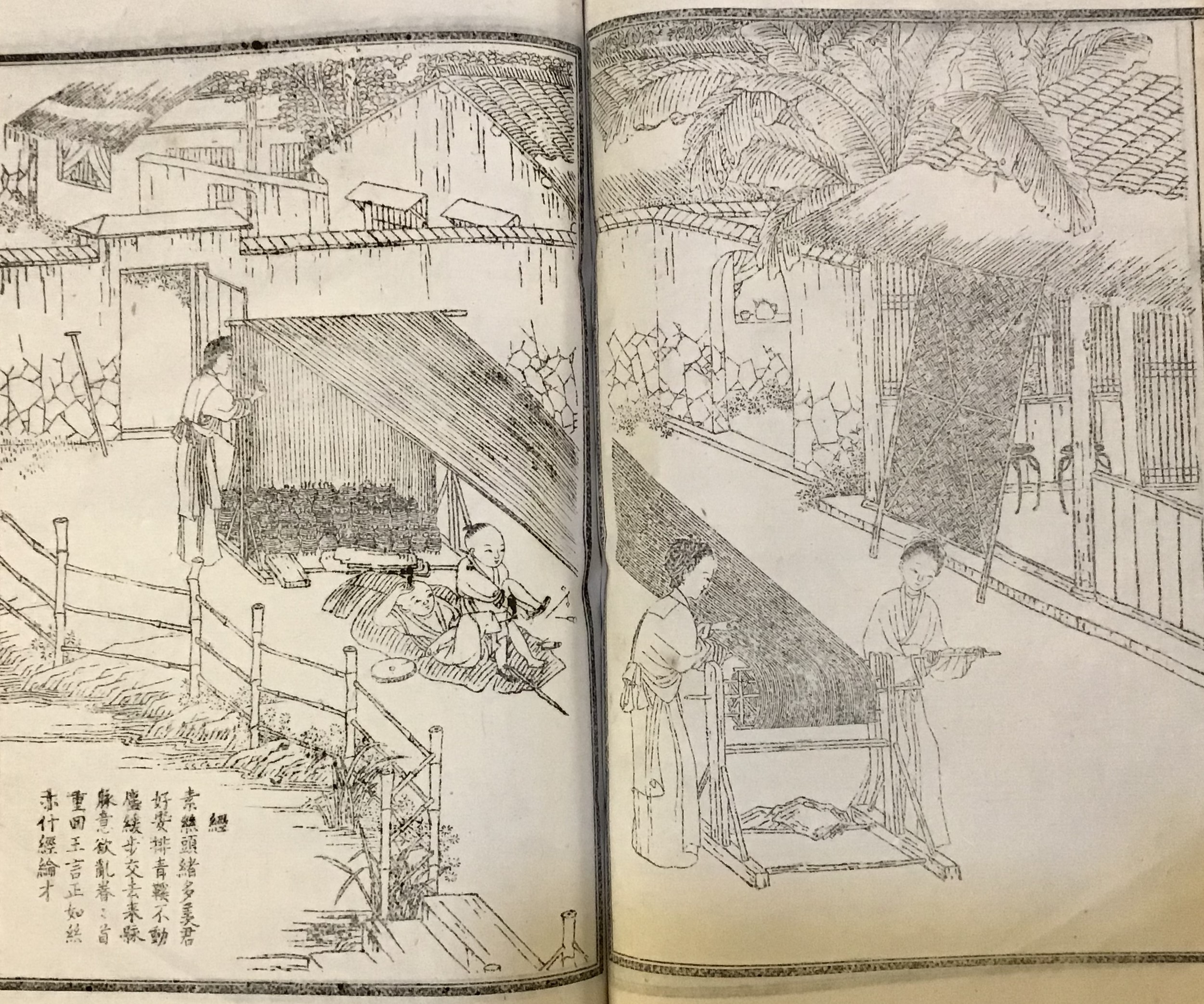

In both texts and images, the intensive agricultural labor is packaged in the idealistic depiction of the pastoral life exemplified by playing kids, well-kept houses, lush vegetation, and joyful working scenes. Certain scenes in this set are emulations of the canonical painting of this genre, The Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Farming and Weaving (Yuzhi gengzhi tu 御製耕織圖), commissioned by Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661-1722) in the 1690s (Figures 4-5). These manuals were manifestations of state control of agriculture, manufacture, and public time; they might not function as practical guide for cultivation.

The Imperial Inscribed Illustrations of Cotton was circulated widely through rubbings and prints. The exquisitely executed carving and Qianlong’s enthusiastic endorsement facilitated mass production of the rubbings. Based on the stone carving, a printed edition titled The Imperially Edited Expanded Instruction on Giving out Clothing (Qinding shouyi guanxun 欽定授衣廣訓) was made during the Jiaqing era (r. 1796-1820).

Figure 4: “Making a warp” (Zhi jing 織經), in The Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Farming and Weaving, detail. Shenbao edition, 19--, Leiden University Libraries.

Figure 5: “Applying Starch” (Bu jiang 佈漿), in The Imperially Inscribed Illustrations of Cotton.

Further readings:

Bussagli, Mario. Cotton and Silk Making in Manchu China (New York: Rizzoli, 1980).

Yan Zhongping 嚴中平. Zhongguo mianfangzhi shigao 中國棉紡織史稿 (Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 1963).

Zurndorfer, Harriet T. “Cotton Textile Manufacture and Marketing in Late Imperial China and the ‘Great Divergence’.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 2011, Vol.54(5): 701-738.

Blog post by: Dr. Lin Fan, University Lecturer at the Leiden Institute for Area Studies