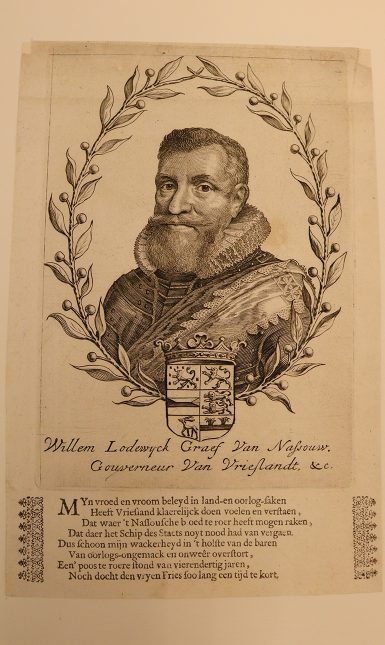

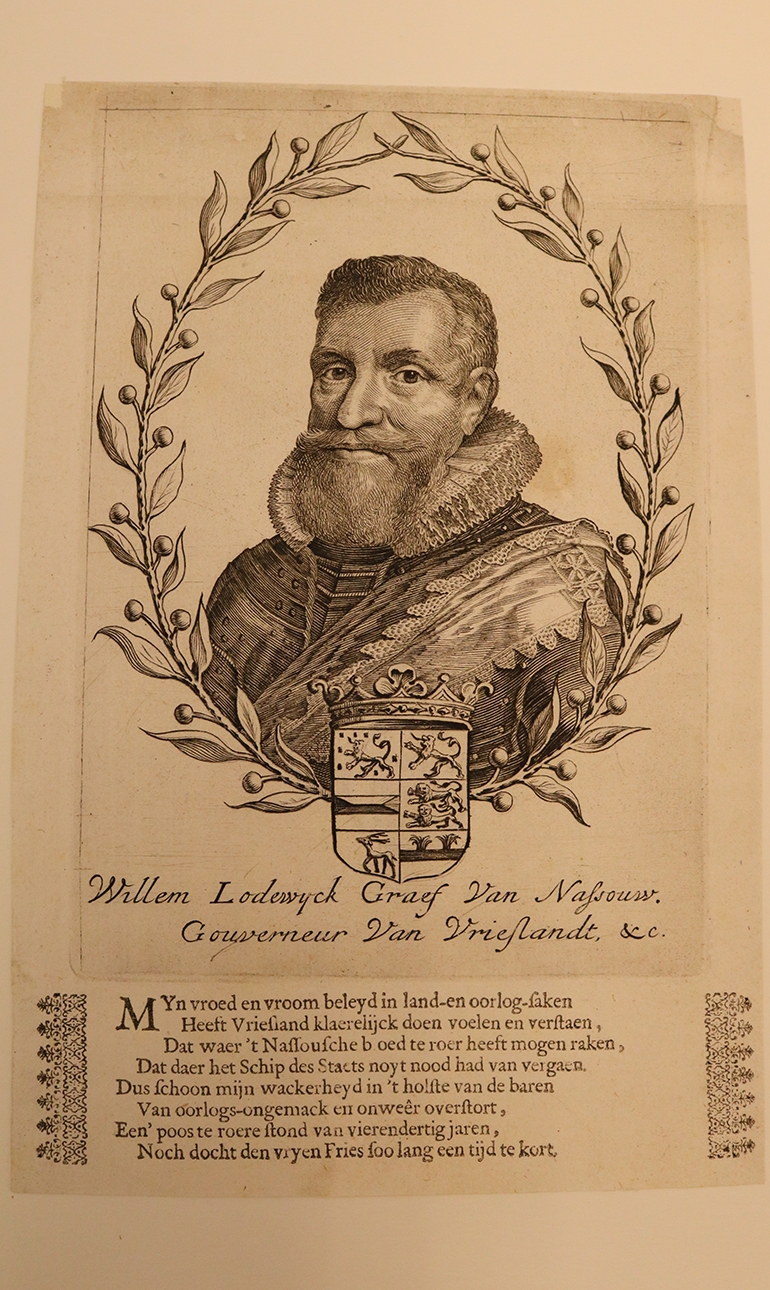

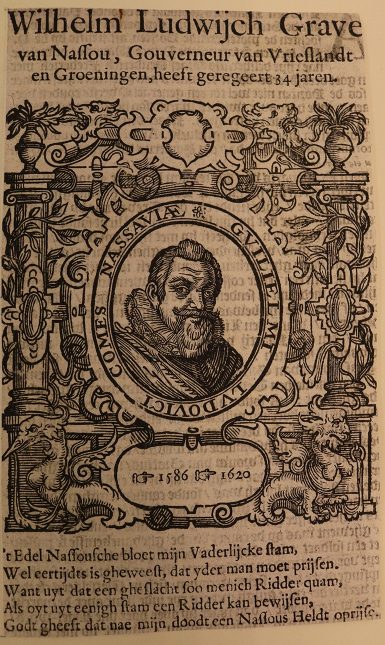

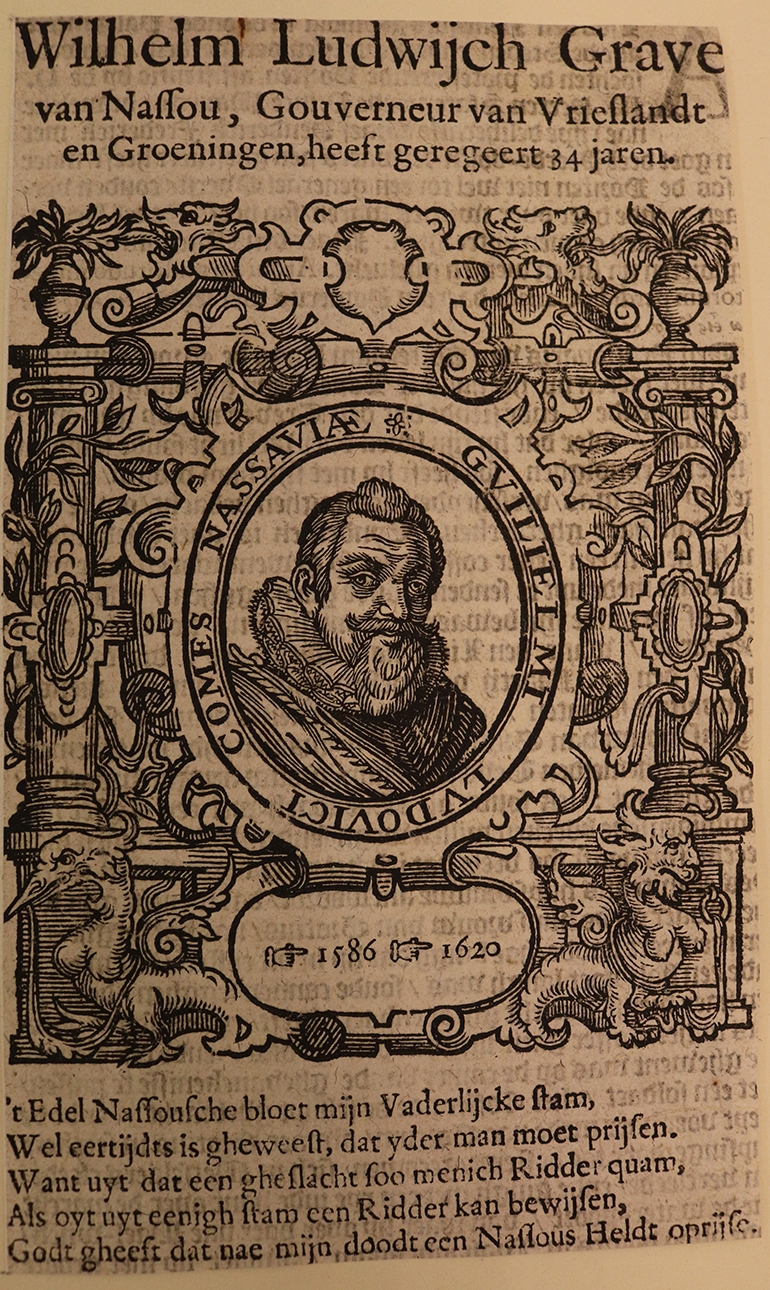

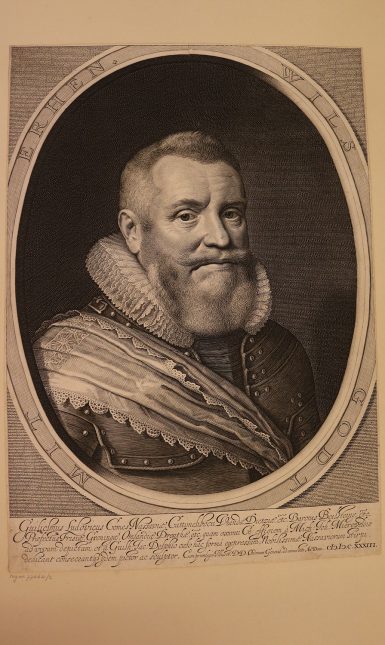

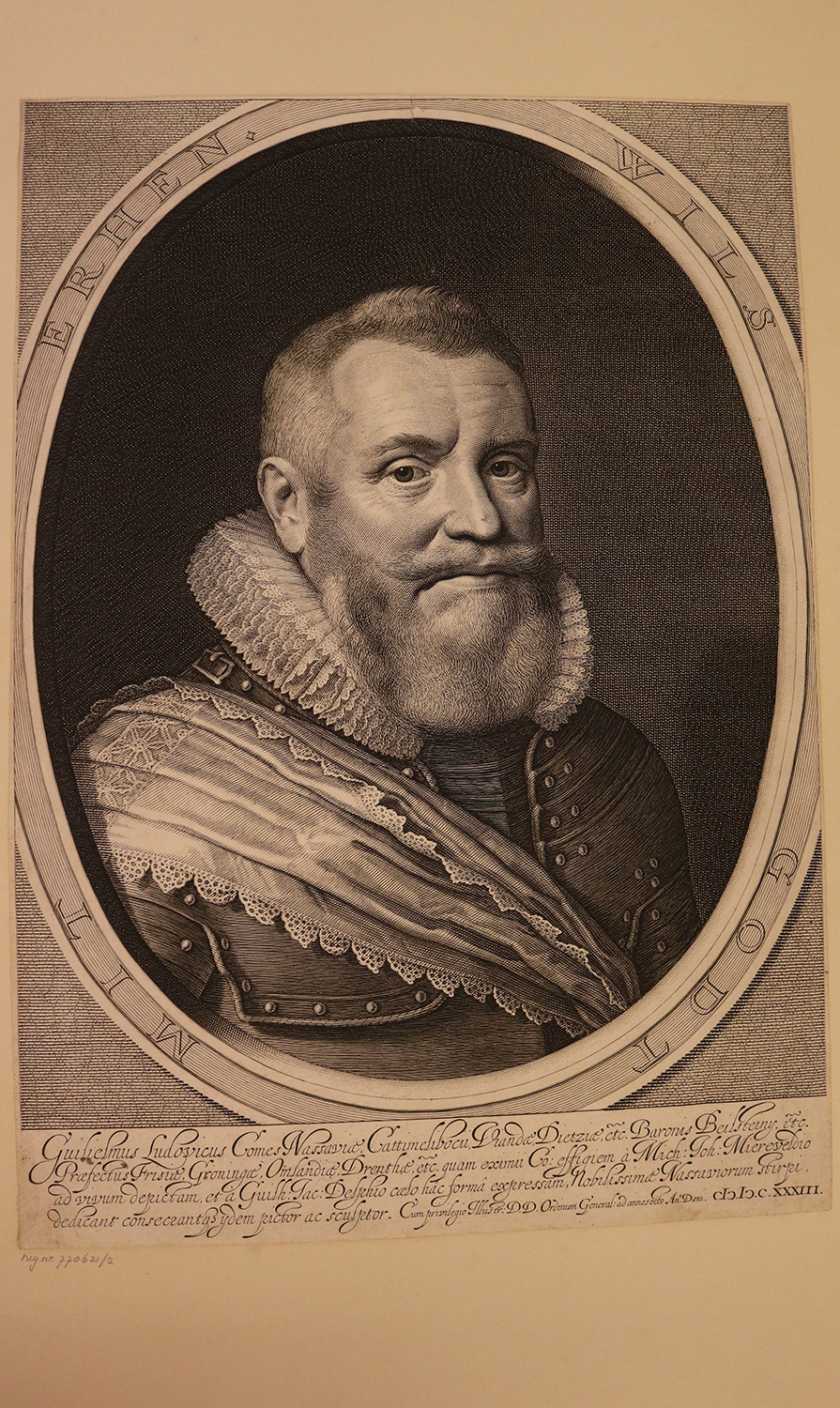

William Louis of Nassau (1560-1620), Saviour of the Dutch Republic

After the assassination of William of Orange (1533-1584), friends feared, and foes hoped the Dutch Republic would collapse. The Republic, however, was saved by a team of professional leaders, laying the foundations for an emergent country and its lasting independence.

After the assassination of William of Orange (1533-1584), leader of the Revolt in the Netherlands, on 10 July 1584, friends feared, and foes hoped the Dutch Republic would collapse. The Republic, however, was saved, first by the international situation; second by a team of professional leaders, who knew how to turn a defensive war into an aggressive one. Doing so, they laid the foundations for an emergent country and its lasting independence.

When the Prince of Orange died, he was not just governor of Holland, Zeeland, and Utrecht, but also of Friesland, a province in the north of the Netherlands. Shortly before his death, he had appointed, on 11 February 1584, his nephew William Louis of Nassau, the oldest son of John of Nassau, Orange’s brother, as his substitute. At the time, William Louis was only 23, and still receiving his education at the court of William of Orange in Antwerp and Delft. He knew by experience how Prince William, before dealing with the Council of State, with the deputies of his provinces or with ambassadors, discussed things political and military with a team of advisors. Thus, well prepared he tried to come to decisions that were based on mutual understanding and shared convictions, a policy of bottom-up, not top-down decision making.

As William of Orange had regularly claimed, the Netherlands could not win the war against the Spanish empire by their own force. Only when France would start a war against Spain as well, they would have a chance. This happened in 1588 because Philip II could not accept the ascendance of Protestant Henry of Navarre to the French throne. The Spanish king ordered his successful commander in the Southern Netherlands, Alexander Farnese (1545-1592), Duke of Parma, who had reconquered Antwerp for Philip II, to intervene in northern France.

Shortly after, William Louis and Maurice attended a meeting of the States-General in The Hague, where they pleaded to start an active war against Spain. Until then, the forces of the rebel provinces were not strong enough to do so. They had fortified their own defenses and could just wait, and see where they had to undergo the next siege or attack. Now, with the enemy occupied, the two military leaders were convinced they could seize the initiative themselves. Their first major victory was the surprise of Breda, by smuggling soldiers into the town, hidden in a peat barge.

How to besiege or to defend a fortified town was not a matter of waging and daring anymore: it became a real science of castrametation: how to build fortifications to endure a siege as long as possible until the enemy would give up, or until rescuing forces came to relieve the town. Equally important was the reorganisation of the armies, splitting them up in smaller units, and having them exercised in marching, shooting, and the following of all kinds of commands in the same manner at exactly the same moment. William Louis and Maurice studied military authors of ancient Greece and Rome to learn from proven examples. Moreover, unheard of until that time: the forces learned and were paid to dig walls of defense, or trenches to undermine the fortifications of beleaguered towns.

We cannot imagine how open 16th century Friesland was to enemy attacks from the adjacent provinces of Groningen and Overijssel. During his governorship of Friesland and Groningen from 1584 until 1620, William Louis knew – remembering how William of Orange had done it – how to approach internal problems between different factions in one town, between several towns within his province, between the provinces of Friesland and Groningen, and between the town and the countryside of Groningen. In military life, he was always where he had to be, showing personal courage when facing the enemy. His reputation became so renowned that enemies outside Friesland preferred only to attack when they knew he was outside his own province.

Being governor of Friesland and therefore a servant of the States of Friesland, he didn’t have the high command. By his patience, benevolence, tenacity and impartiality over the years, however, he earned the respect of the States of Friesland and their inhabitants. Although a fervent Calvinist himself, he followed the example of prince William of Orange by not disturbing Roman Catholics and Mennonites.

Together with Maurice, he had to obey the supreme orders of the States-General. This highest college of state decided where to command the Republic’s army. When the States of Friesland wanted to besiege the town of Groningen in 1593, the States-General decided first to conquer the town of Geertruidenberg, near Brabant. Every province had to await its turn. Groningen would fall in 1594. William Louis and Maurice even succumbed to commands when these, in their own eyes, were contradictory to the military security of the Dutch Republic. This happened in 1600 when Grand pensionary Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and the States-General ordered the seizure of the town of Dunkirk, far south in enemy territory. Maurice went with the army – William Louis stayed in the Republic as a safeguard. The 1600 Battle of Nieuwpoort (in present-day West-Flanders) – famous in Dutch history – saved appearances for the prince and the country, but the lesson was obvious: no top-down government, neither by princes nor by burghers.

Finally, William Louis not only showed himself to be a great political and military leader. He was also a man with a great heart. In the conflict between Prince Maurice and Oldenbarnevelt in 1618/9, William Louis thought the execution of the grey statesman was undeserved and pleaded to save his life. Alas, without result. Beloved by his provinces and regretted by the entire Republic, William Louis died on 31 May 1620, now 400 years ago. In Friesland, he is remembered to this very day as “ús heit”, our father, pater patriae.

More information: www.willemlodewijkjaar.nl. Website: www.dutchrevolt.edu.

Further reading: Lem, Anton van der, Revolt in the Netherlands, The Eighty Years War 1568-1648, (Reaktionbooks, 2018)